The End Result Of Meiosis Is

listenit

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The End Result of Meiosis: Four Unique Haploid Gametes

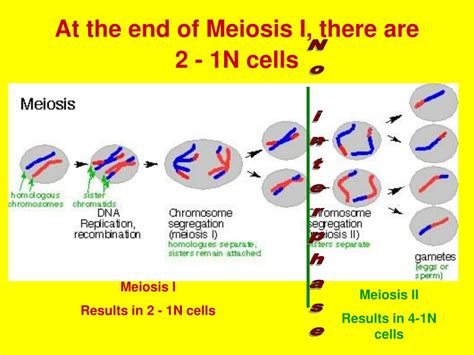

Meiosis, a specialized type of cell division, is fundamental to sexual reproduction. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical daughter cells, meiosis generates four genetically unique haploid cells. This crucial process ensures genetic diversity within a species and plays a vital role in the inheritance of traits from one generation to the next. Understanding the end result of meiosis—four unique haploid gametes—requires a deeper dive into the two distinct stages of this complex process: Meiosis I and Meiosis II.

Meiosis I: Reductional Division

Meiosis I is characterized by the reduction of chromosome number. It begins with a diploid cell (2n), containing two sets of chromosomes—one from each parent. The intricate process of Meiosis I can be broken down into several key phases:

Prophase I: A Tale of Two Chromosomes

Prophase I is the longest and most complex phase of meiosis I. It's here that the magic of genetic recombination truly unfolds. Several key events define Prophase I:

-

Chromatin Condensation: The replicated chromosomes, each consisting of two sister chromatids joined at the centromere, begin to condense and become visible under a microscope.

-

Synapsis: Homologous chromosomes, one from each parent, pair up precisely, forming a structure called a bivalent or tetrad. This pairing is crucial for the next step.

-

Crossing Over: This is the hallmark of Meiosis I and the primary source of genetic variation. Non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes exchange segments of DNA at points called chiasmata. This process, called crossing over or recombination, shuffles alleles between homologous chromosomes, creating new combinations of genes. The precise location and frequency of crossing over contribute significantly to the uniqueness of the resulting gametes.

-

Formation of the Chiasmata: The physical manifestation of crossing over are the chiasmata, which hold the homologous chromosomes together. These chiasmata are essential for proper chromosome segregation in the subsequent anaphase I.

-

Nuclear Envelope Breakdown: Towards the end of Prophase I, the nuclear envelope breaks down, releasing the chromosomes into the cytoplasm.

Metaphase I: Chromosomes Align

In Metaphase I, the homologous chromosome pairs (bivalents) align along the metaphase plate, a plane equidistant from the two poles of the cell. The orientation of each homologous pair on the metaphase plate is random, a phenomenon known as independent assortment. This random arrangement contributes significantly to the genetic variation in the resulting gametes. Each homologous pair has a 50/50 chance of orienting towards either pole, leading to a vast number of possible chromosome combinations in the daughter cells.

Anaphase I: Homologous Chromosomes Separate

Anaphase I marks the separation of homologous chromosomes. The chiasmata break, and each homologous chromosome, consisting of two sister chromatids, moves to opposite poles of the cell. It's crucial to note that sister chromatids remain attached at the centromere. This contrasts with Anaphase in mitosis, where sister chromatids separate. The reduction in chromosome number from 2n to n occurs during Anaphase I.

Telophase I and Cytokinesis: Two Haploid Cells

Telophase I involves the arrival of chromosomes at the poles of the cell. The nuclear envelope may or may not reform, and the chromosomes may or may not decondense. Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, follows Telophase I, resulting in two haploid daughter cells (n). Each daughter cell contains only one chromosome from each homologous pair, but each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids. It is important to reiterate that these two daughter cells are genetically different from each other and from the parent cell due to crossing over and independent assortment.

Meiosis II: Equational Division

Meiosis II is much more similar to mitosis. It involves the separation of sister chromatids and results in four haploid daughter cells. While genetically distinct from each other, the events of Meiosis II are less influential in generating genetic diversity compared to Meiosis I.

Prophase II: Chromosomes Condense

In Prophase II, the chromosomes, each still composed of two sister chromatids, condense. The nuclear envelope (if reformed during Telophase I) breaks down, and the spindle apparatus begins to form.

Metaphase II: Chromosomes Align

In Metaphase II, the individual chromosomes align along the metaphase plate. Unlike Meiosis I, the chromosomes align individually, not as pairs.

Anaphase II: Sister Chromatids Separate

In Anaphase II, the sister chromatids finally separate at the centromere and move towards opposite poles of the cell. This is similar to the separation of sister chromatids during mitosis.

Telophase II and Cytokinesis: Four Haploid Gametes

Telophase II involves the arrival of chromosomes at the poles of the cell. The nuclear envelope reforms, and the chromosomes decondense. Cytokinesis follows, resulting in the formation of four haploid daughter cells (n). Each of these daughter cells contains a single set of chromosomes, and each chromosome is composed of a single chromatid. These haploid cells are the gametes—sperm in males and egg cells (ova) in females. The key takeaway is that these four gametes are genetically unique due to the events of crossing over and independent assortment during Meiosis I.

The Significance of Genetic Variation

The end result of meiosis, four genetically unique haploid gametes, is not merely a biological fact; it's a cornerstone of evolution. The genetic variation generated through:

-

Crossing Over: This process shuffles alleles between homologous chromosomes, creating new combinations of genes that were not present in the parent cell.

-

Independent Assortment: The random orientation of homologous chromosome pairs during Metaphase I exponentially increases the potential genetic diversity among the resulting gametes.

is crucial for several reasons:

-

Adaptation to Changing Environments: Genetic variation provides the raw material for natural selection. Individuals with advantageous gene combinations are more likely to survive and reproduce in changing environments, leading to adaptation and evolution of the species.

-

Resistance to Diseases: Genetic diversity within a population makes it less susceptible to widespread disease outbreaks. If all individuals were genetically identical, a single disease could wipe out the entire population.

-

Species Survival: Genetic variation ensures the long-term survival of a species by enabling it to adapt to various environmental pressures and challenges.

Errors in Meiosis: Consequences and Implications

While meiosis is a highly regulated process, errors can occur. These errors can lead to changes in chromosome number (aneuploidy), such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), or structural changes in chromosomes. Such errors can have serious consequences, ranging from developmental abnormalities to infertility. The mechanisms that ensure the accuracy of meiosis are complex and involve a number of checkpoints and repair systems. However, occasional errors are inevitable, highlighting the delicate balance involved in generating genetically diverse yet structurally sound gametes.

Conclusion: The Power of Meiosis

Meiosis is a remarkable process that seamlessly combines reduction of chromosome number with the generation of genetic diversity. The end result – four genetically unique haploid gametes – is the foundation of sexual reproduction and is critical for the adaptation, survival, and evolution of sexually reproducing organisms. Understanding the intricacies of meiosis, from the complexities of Prophase I to the final separation of sister chromatids in Anaphase II, is fundamental to understanding the mechanisms that underpin the incredible diversity of life on Earth. The random nature of crossing over and independent assortment ensures that each gamete is a unique combination of genetic material, a testament to the elegance and power of this fundamental biological process. This inherent genetic variability is the driving force behind evolution, shaping the characteristics of species across generations and allowing them to thrive in ever-changing environments. The precision and complexity of meiosis, coupled with its inherent capacity for generating genetic diversity, make it a truly awe-inspiring aspect of the biological world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Valence Electros In Hydrogen

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Do Animals Get The Nitrogen They Need

Mar 17, 2025

-

Nucleotides Are Attached By Bonds Between The

Mar 17, 2025

-

The Sum Of A Number And Four

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Many Electrons Can Each Ring Hold

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The End Result Of Meiosis Is . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.