Why Does Active Transport Need Energy

listenit

Mar 15, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Why Does Active Transport Need Energy? A Deep Dive into Cellular Processes

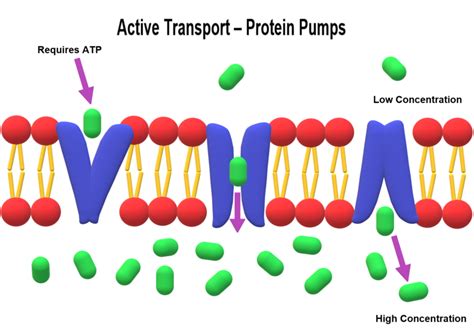

Active transport, a fundamental process in all living cells, is responsible for the movement of molecules across cell membranes against their concentration gradient. This means moving substances from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration – the opposite of what would happen naturally through passive transport. Unlike passive transport, which relies on diffusion and osmosis, active transport requires energy input to overcome the inherent resistance to this uphill movement. But why exactly is this energy necessary? This article will delve deep into the mechanics of active transport, exploring the various types, the roles of ATP and other energy sources, and the critical implications of this energy-demanding process for cellular function and overall organismal health.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Concentration Gradients and Membrane Permeability

Before delving into the energy requirements of active transport, let's establish a strong foundation. Cells are enclosed by selectively permeable membranes—barriers that regulate the passage of substances into and out of the cell. These membranes are primarily composed of a lipid bilayer with embedded proteins. Some substances can passively cross the membrane through simple diffusion (small, nonpolar molecules) or facilitated diffusion (with the help of membrane proteins). However, many essential molecules, such as ions (sodium, potassium, calcium), glucose, and amino acids, need to be transported against their concentration gradients. This necessitates active transport.

A concentration gradient refers to the difference in the concentration of a substance between two areas. Substances naturally tend to move from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration, following their concentration gradient. This movement aims to reach equilibrium, where the concentration is uniform. Active transport, therefore, is an uphill battle against this natural tendency.

The Energetic Hurdles: Why Passive Transport Isn't Enough

Passive transport mechanisms are efficient for moving substances down their concentration gradients. They don't require cellular energy because they leverage the inherent kinetic energy of molecules and the natural tendency towards equilibrium. However, maintaining proper intracellular conditions often demands moving substances against their concentration gradients. This is where the energy requirement of active transport becomes crucial.

Several reasons necessitate this "uphill" movement:

-

Maintaining Cellular Homeostasis: Cells need to carefully regulate the concentration of ions (sodium, potassium, calcium, etc.) and other molecules inside the cell. This is critical for maintaining the proper osmotic balance, preventing cell lysis (bursting) or crenation (shrinking). Active transport mechanisms actively pump ions in or out to precisely control intracellular concentrations.

-

Nutrient Uptake: Cells require specific nutrients (glucose, amino acids) for growth, repair, and energy production. These nutrients may exist at low concentrations in the surrounding environment. Active transport enables cells to accumulate these vital substances, even when the extracellular concentration is low. This is particularly important in the gut, where nutrient absorption from the digested food is facilitated by active transport mechanisms.

-

Waste Removal: Metabolic processes generate waste products that need to be removed from the cell to prevent toxicity. Active transport plays a critical role in actively pumping out these waste products against their concentration gradients.

-

Neurotransmission: The nervous system relies heavily on active transport mechanisms to maintain the electrochemical gradients necessary for nerve impulse transmission. The sodium-potassium pump, a vital component of neuronal function, actively pumps sodium ions out and potassium ions into nerve cells, creating the conditions for action potentials.

The Power Source: ATP and Other Energy Carriers

The primary energy source driving most active transport processes is adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the cell's energy currency. It's a high-energy molecule that releases energy when one of its phosphate bonds is hydrolyzed, forming adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). This released energy is then used to power the active transport proteins.

The process generally involves:

-

Binding: The molecule to be transported binds to a specific transport protein embedded in the cell membrane.

-

Conformational Change: The binding of the molecule triggers a conformational change in the transport protein, facilitated by the energy released from ATP hydrolysis. This conformational change moves the molecule across the membrane.

-

Release: Once the molecule is transported to the other side of the membrane, it is released from the transport protein, which reverts to its original conformation.

While ATP is the primary energy source, other energy carriers can also drive active transport in some cases. For example, in some systems, the energy released from the movement of one molecule down its concentration gradient can be coupled to the movement of another molecule against its gradient. This is called secondary active transport, and it doesn't directly involve ATP hydrolysis. Instead, it utilizes the electrochemical gradient established by a primary active transport system (often a sodium-potassium pump).

Types of Active Transport: A Closer Look

Active transport mechanisms can be broadly categorized into two main types:

1. Primary Active Transport: Direct ATP Hydrolysis

Primary active transport directly utilizes the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to move molecules against their concentration gradient. A classic example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ ATPase). This pump actively transports three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and two potassium ions (K+) into the cell for every ATP molecule hydrolyzed. This creates an electrochemical gradient crucial for maintaining cell volume, nerve impulse transmission, and secondary active transport. Other examples include the calcium pump (Ca2+ ATPase) and the proton pump (H+ ATPase).

2. Secondary Active Transport: Coupled Transport

Secondary active transport doesn't directly use ATP. Instead, it harnesses the energy stored in an electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport. This gradient usually involves ions like sodium (Na+) or protons (H+). The movement of these ions down their concentration gradient provides the energy to transport another molecule against its gradient. There are two main types of secondary active transport:

-

Symport: The transported molecule moves in the same direction as the driving ion. For example, glucose uptake in intestinal cells is coupled to the inward movement of sodium ions.

-

Antiport: The transported molecule moves in the opposite direction as the driving ion. The sodium-calcium exchanger is an example; the inward movement of sodium ions drives the outward movement of calcium ions.

The Significance of Active Transport: Beyond Cellular Processes

The significance of active transport extends far beyond individual cellular processes. It plays a critical role in various physiological functions and overall organismal health:

-

Nutrient Absorption: The absorption of essential nutrients from the digestive tract relies heavily on active transport mechanisms. This ensures efficient uptake of glucose, amino acids, and other vital molecules.

-

Kidney Function: The kidneys use active transport to filter blood, reabsorb essential substances, and excrete waste products. This process is crucial for maintaining the body's fluid balance and electrolyte homeostasis.

-

Nerve Impulse Transmission: As mentioned earlier, active transport is fundamental to nerve impulse transmission. The sodium-potassium pump establishes the electrochemical gradient that drives action potentials.

-

Muscle Contraction: Active transport mechanisms are involved in regulating calcium ion levels within muscle cells, which are essential for muscle contraction and relaxation.

-

Immune Response: Active transport plays a role in immune cell function, enabling the movement of immune cells and molecules to sites of infection or inflammation.

-

Drug Transport: Many drugs rely on active transport mechanisms for absorption, distribution, and elimination from the body. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial in designing effective drug delivery systems.

Malfunctions and Diseases: The Consequences of Active Transport Failure

Dysfunction in active transport mechanisms can have severe consequences for cellular and organismal health. Several diseases are associated with defects in active transport proteins:

-

Cystic Fibrosis: This genetic disorder is caused by a mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, which is involved in chloride ion transport. This leads to impaired fluid secretion, affecting multiple organs.

-

Hyperkalemia: This condition, characterized by elevated potassium levels in the blood, can be caused by defects in the sodium-potassium pump.

-

Cardiac Arrhythmias: Disruptions in ion transport mechanisms, particularly those affecting sodium, potassium, and calcium, can lead to cardiac arrhythmias.

-

Neurological Disorders: Defects in ion channels and pumps involved in neuronal function can contribute to various neurological disorders.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Role of Energy in Active Transport

Active transport is an indispensable process for all living cells. Its ability to move molecules against their concentration gradients is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, enabling nutrient uptake, facilitating waste removal, and driving a plethora of vital physiological functions. The energy requirement inherent in active transport is not merely an incidental feature; it's fundamentally linked to the uphill nature of the process. The hydrolysis of ATP, and in some cases, other energy sources, provides the necessary power to overcome the natural tendency of molecules to move down their concentration gradients, ensuring the proper functioning of cells and the overall health of the organism. Understanding this energy dependency is critical for comprehending the intricate workings of life itself and for developing effective treatments for diseases related to active transport dysfunction.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Proteins Are Made Of Monomers Called

Mar 15, 2025

-

X 2 4 X 2 Graph

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between Ion And Atom

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is 2 3 Of 10

Mar 15, 2025

-

1 1 3 Cups Divided By 2

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Why Does Active Transport Need Energy . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.