How Does A Igneous Rock Become A Sedimentary Rock

listenit

Mar 24, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Amazing Journey: How Igneous Rocks Transform into Sedimentary Rocks

The Earth's crust is a dynamic tapestry woven from a variety of rocks, each with its own unique story to tell. Among these, igneous and sedimentary rocks represent two fundamental rock types, born through vastly different processes. While seemingly disparate, they are linked in a remarkable cycle of transformation, a continuous dance of creation and destruction driven by Earth's internal and external forces. This article delves into the fascinating journey of an igneous rock's metamorphosis into a sedimentary rock, exploring the intricate steps involved and the geological forces that shape our planet.

From Molten Magma to Solid Igneous Rock: The Starting Point

Our story begins with igneous rocks, formed from the cooling and solidification of molten magma or lava. Magma, a subterranean molten rock, rises from the Earth's mantle, often finding its way to the surface through volcanic eruptions. Lava, the extrusive equivalent of magma, cools rapidly upon contact with the atmosphere, forming volcanic rocks like basalt and obsidian. Conversely, magma that cools slowly beneath the Earth's surface forms intrusive igneous rocks such as granite and gabbro, characterized by larger crystal sizes due to the slower cooling rates. These igneous rocks, with their varied compositions and textures, represent the initial stage in our transformation saga.

Key Characteristics of Igneous Rocks Relevant to Sedimentary Transformation:

- Composition: The mineral composition of the igneous rock is crucial. Rocks rich in quartz and feldspar, for instance, will weather and erode differently than those dominated by mafic minerals like olivine and pyroxene.

- Texture: The size and arrangement of crystals (grain size) influences the rock's resistance to weathering and erosion. Fine-grained rocks tend to weather more rapidly than coarse-grained ones.

- Hardness: The hardness of the constituent minerals affects the rate at which the rock breaks down. Harder minerals will resist weathering longer.

The Long Road to Sedimentation: Weathering and Erosion

The transformation from igneous to sedimentary rock commences with the relentless processes of weathering and erosion. Weathering is the breakdown of rocks at or near the Earth's surface, while erosion is the transportation of the weathered material. These processes are driven by several powerful forces:

1. Mechanical Weathering: Physical Breakdown

Mechanical weathering, also known as physical weathering, involves the disintegration of rocks without any change in their chemical composition. Several agents contribute to this process:

- Freeze-thaw cycles: Water seeps into cracks in the igneous rock. When the water freezes, it expands, widening the cracks and eventually fracturing the rock.

- Abrasion: Rocks are constantly bombarded by other rocks, wind-blown sand, or even ice, causing them to break down into smaller pieces. This is particularly effective in high-energy environments like rivers and glaciers.

- Exfoliation: As pressure is released from overlying rock layers, the underlying igneous rock expands and cracks, leading to the peeling off of concentric layers. This is common in granite formations.

2. Chemical Weathering: Chemical Alteration

Chemical weathering involves the decomposition of rocks through chemical reactions. This alters the mineral composition of the igneous rock, creating new minerals that are more stable at the Earth's surface. Key processes include:

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals, breaking them down and forming clay minerals. Feldspars, a common component of igneous rocks, are particularly susceptible to hydrolysis.

- Oxidation: Oxygen reacts with minerals, causing them to change color and often become weaker. Iron-rich minerals are commonly affected by oxidation, leading to the reddish or brownish hues often seen in weathered rocks.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide dissolved in rainwater forms a weak carbonic acid, which reacts with certain minerals, like calcite, dissolving them.

Transportation and Deposition: Shaping the Sediment

The weathered and eroded fragments of the igneous rock, now in the form of sediments, are transported by various agents:

- Water: Rivers, streams, and ocean currents carry sediments vast distances, sorting them by size and density. Larger, heavier particles are deposited closer to the source, while finer particles are transported further.

- Wind: Wind transports fine-grained sediments like sand and dust, often creating vast sand dunes or loess deposits.

- Ice: Glaciers act as powerful agents of erosion and transport, carrying a wide range of sediment sizes over long distances. Glacial deposits are often unsorted mixtures of different sediment sizes.

- Gravity: Mass wasting events, such as landslides and rockfalls, transport sediments downslope.

Once the transporting agent loses its energy, the sediments are deposited in various environments:

- Continental environments: Rivers, lakes, and deserts are common depositional environments, creating sedimentary rocks like sandstone, shale, and conglomerate.

- Marine environments: Oceans and seas accumulate vast quantities of sediments, forming sedimentary layers that can eventually become thick sedimentary rock formations.

Lithification: From Loose Sediment to Solid Rock

The final stage in the transformation involves lithification, the process by which loose sediment is converted into solid rock. This is a complex process involving several stages:

- Compaction: As more and more sediment is deposited, the weight of the overlying layers compresses the underlying sediments, squeezing out water and reducing the pore space between particles.

- Cementation: Dissolved minerals in groundwater precipitate within the pore spaces, acting as a cement that binds the sediment particles together. Common cementing agents include calcite, silica, and iron oxides.

- Recrystallization: Minerals within the sediment can recrystallize, forming larger crystals and further strengthening the rock.

Types of Sedimentary Rocks Derived from Igneous Rocks: A Diverse Outcome

The sedimentary rocks ultimately formed from the igneous precursor will depend on several factors: the composition of the original igneous rock, the type and intensity of weathering and erosion, the transportation mechanism, and the depositional environment. Some common sedimentary rocks derived from igneous sources include:

- Sandstone: Formed from the accumulation and lithification of sand-sized grains, often derived from the weathering of felsic igneous rocks like granite.

- Shale: Formed from the accumulation and lithification of clay-sized particles, often resulting from the chemical weathering of feldspar-rich igneous rocks.

- Conglomerate: Formed from the lithification of a mixture of rounded pebbles and cobbles, often representing the deposition of weathered fragments of a variety of igneous rocks.

- Arkose: A type of sandstone that contains a significant amount of feldspar, indicating rapid erosion and deposition of relatively unaltered weathered granite.

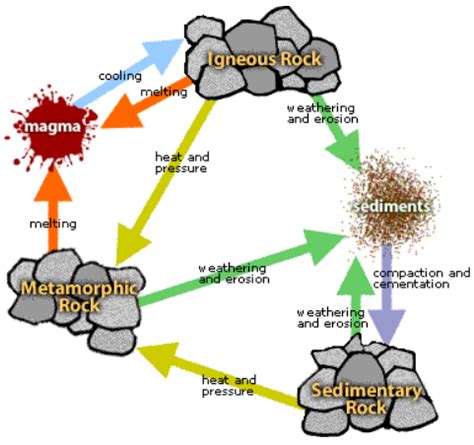

The Rock Cycle: A Continuous Transformation

The transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is not a one-way street. It's part of the larger rock cycle, a continuous process where rocks are formed, transformed, and destroyed. Sedimentary rocks themselves can be metamorphosed into metamorphic rocks under intense heat and pressure, or even melted to form new igneous rocks. This cycle, driven by plate tectonics, weathering, erosion, and other geological forces, is a testament to the dynamic nature of our planet and the interconnectedness of its geological processes.

Conclusion: A Journey of Transformation

The journey from igneous rock to sedimentary rock is a testament to the incredible power of geological processes. It's a story of weathering, erosion, transportation, deposition, and lithification, a sequence of events that transforms solid rock into sediment and then back into solid rock, albeit with a completely new identity. Understanding this transformation deepens our appreciation for the complexity of Earth's systems and the continuous reshaping of our planet's surface. This intricate process is a crucial part of the Earth's rock cycle, connecting different rock types and highlighting the dynamic interplay between internal and external forces that shape our world. The study of these transformations offers invaluable insights into Earth’s history and its ongoing evolution.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Calculate The Molar Ratio

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Is 0 16666 As A Fraction

Mar 25, 2025

-

Common Multiples Of 7 And 9

Mar 25, 2025

-

How Many Protons Does Hg Have

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Is The Perimeter Of Rectangle Jklm

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Does A Igneous Rock Become A Sedimentary Rock . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.