Atoms That Gain Or Lose Electrons Are Known As

listenit

Mar 21, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Atoms That Gain or Lose Electrons Are Known As Ions: A Deep Dive into Ionic Bonding and its Implications

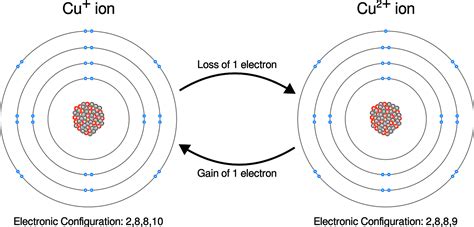

Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of matter, the tiny particles that make up everything around us. Each atom consists of a nucleus containing protons and neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of orbiting electrons. While the number of protons defines the element, the number of electrons plays a crucial role in determining an atom's chemical behavior and how it interacts with other atoms. Atoms that gain or lose electrons are known as ions, and their formation is the basis for a significant type of chemical bonding known as ionic bonding. Understanding ions and ionic bonding is crucial for grasping many fundamental concepts in chemistry, physics, and materials science.

What are Ions? A Closer Look at Charged Particles

The term "ion" refers to an atom or molecule that carries a net electrical charge. This charge arises from an imbalance between the number of protons and electrons. Remember that protons carry a positive charge (+1) and electrons carry a negative charge (-1). Neutrons are electrically neutral.

-

Cations: When an atom loses one or more electrons, it becomes positively charged because it now has more protons than electrons. These positively charged ions are called cations. The number of positive charges indicates how many electrons were lost. For example, a calcium atom (Ca) that loses two electrons becomes a calcium cation (Ca²⁺).

-

Anions: Conversely, when an atom gains one or more electrons, it becomes negatively charged because it now has more electrons than protons. These negatively charged ions are called anions. The number of negative charges indicates how many electrons were gained. For example, a chlorine atom (Cl) that gains one electron becomes a chloride anion (Cl⁻).

How Ions are Formed: The Role of Electron Configuration

The formation of ions is primarily driven by the tendency of atoms to achieve a stable electron configuration. Atoms are most stable when their outermost electron shell (valence shell) is completely filled. This stable arrangement is often referred to as a "noble gas configuration," because it mimics the electron configuration of the noble gases (Group 18 elements) which are exceptionally unreactive.

Atoms with nearly full or nearly empty valence shells are particularly prone to forming ions. Atoms readily lose or gain electrons to achieve the stable electron configuration of a nearby noble gas. This process is energetically favorable, leading to the formation of ions and subsequent ionic bonds.

-

Metals and Cations: Metals, generally located on the left side of the periodic table, tend to have relatively few electrons in their valence shell. They readily lose these electrons to achieve a stable configuration, forming positively charged cations. Group 1 metals (alkali metals) like sodium (Na) readily lose one electron to become Na⁺, while Group 2 metals (alkaline earth metals) like magnesium (Mg) readily lose two electrons to become Mg²⁺.

-

Nonmetals and Anions: Nonmetals, generally located on the right side of the periodic table, tend to have nearly full valence shells. They readily gain electrons to complete their valence shell and achieve a stable configuration, forming negatively charged anions. Group 17 elements (halogens) like chlorine (Cl) readily gain one electron to become Cl⁻, while Group 16 elements (chalcogens) like oxygen (O) readily gain two electrons to become O²⁻.

Ionic Bonding: The Electrostatic Attraction that Holds Ions Together

Once ions are formed, they are not independent entities. The strong electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions results in the formation of ionic bonds. These bonds hold the ions together in a crystal lattice structure, forming ionic compounds.

The strength of an ionic bond depends on several factors, including:

-

Charge magnitude: The higher the charge of the ions (e.g., 3+ and 3- versus 1+ and 1-), the stronger the electrostatic attraction and thus the stronger the ionic bond.

-

Ionic radius: The smaller the ions, the closer they can get to each other, leading to stronger electrostatic attraction and a stronger ionic bond. Smaller ions have a higher charge density.

Properties of Ionic Compounds: A Consequence of Ionic Bonding

The strong electrostatic forces in ionic compounds lead to several characteristic properties:

-

High melting and boiling points: A significant amount of energy is required to overcome the strong electrostatic forces holding the ions together, resulting in high melting and boiling points.

-

Crystalline structure: Ionic compounds typically form crystalline solids with a regular, repeating arrangement of ions. This ordered arrangement maximizes the electrostatic attraction between the oppositely charged ions.

-

Hardness and brittleness: While strong in their crystal structure, ionic compounds are brittle because the displacement of layers of ions can cause repulsion between similarly charged ions, leading to fracture.

-

Solubility in water: Many ionic compounds are soluble in water because water molecules can surround and interact with the ions, weakening the electrostatic forces holding them together.

-

Electrical conductivity: Ionic compounds generally conduct electricity when molten or dissolved in water because the ions are free to move and carry an electric charge. In solid state, they are poor conductors because the ions are fixed in the crystal lattice.

Examples of Ions and Ionic Compounds

Let's illustrate the concepts with some specific examples:

-

Sodium chloride (NaCl): Sodium (Na), an alkali metal, loses one electron to form Na⁺. Chlorine (Cl), a halogen, gains one electron to form Cl⁻. The electrostatic attraction between Na⁺ and Cl⁻ forms the ionic compound sodium chloride, or common table salt.

-

Magnesium oxide (MgO): Magnesium (Mg), an alkaline earth metal, loses two electrons to form Mg²⁺. Oxygen (O), a chalcogen, gains two electrons to form O²⁻. The electrostatic attraction between Mg²⁺ and O²⁻ forms the ionic compound magnesium oxide.

-

Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃): Aluminum (Al) loses three electrons to form Al³⁺. Oxygen (O) gains two electrons to form O²⁻. To achieve charge neutrality, the ratio of aluminum to oxygen ions is 2:3, resulting in the formula Al₂O₃.

Beyond Simple Ions: Polyatomic Ions and Complex Ionic Compounds

While the examples above focus on simple monoatomic ions (ions consisting of a single atom), many important ions are polyatomic – meaning they consist of multiple atoms covalently bonded together, carrying a net charge.

Examples of polyatomic ions include:

-

Hydroxide (OH⁻): A negatively charged ion consisting of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom.

-

Nitrate (NO₃⁻): A negatively charged ion consisting of one nitrogen atom and three oxygen atoms.

-

Sulfate (SO₄²⁻): A negatively charged ion consisting of one sulfur atom and four oxygen atoms.

-

Ammonium (NH₄⁺): A positively charged ion consisting of one nitrogen atom and four hydrogen atoms.

These polyatomic ions can combine with other ions (both monoatomic and polyatomic) to form a wide variety of complex ionic compounds. For instance, ammonium nitrate (NH₄NO₃) is formed by the combination of ammonium cation (NH₄⁺) and nitrate anion (NO₃⁻).

The Importance of Ions in Biological Systems

Ions play vital roles in various biological processes. For example:

-

Nerve impulse transmission: The movement of sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) ions across cell membranes is crucial for nerve impulse transmission.

-

Muscle contraction: Calcium (Ca²⁺) ions are essential for muscle contraction.

-

Enzyme function: Many enzymes require specific ions as cofactors to function properly.

-

Osmotic balance: The balance of ions within and outside cells is critical for maintaining osmotic balance, preventing cell damage.

-

Blood clotting: Calcium (Ca²⁺) ions are essential for blood clotting.

Ions in Everyday Life: Applications and Impact

Ions are not just confined to scientific laboratories and biological systems; they play a significant role in our daily lives. Their presence is felt in many applications:

-

Electrolytes: Electrolytes, which are solutions containing ions, are vital components in many products, from sports drinks to batteries.

-

Metal extraction: The extraction of metals from their ores often involves ionic processes.

-

Fertilizers: Many fertilizers contain ionic compounds that provide essential nutrients to plants.

-

Water treatment: Ions play an important role in water treatment processes, including softening and purification.

-

Medical imaging: Certain types of medical imaging, such as X-rays and CT scans, rely on the interaction of X-rays with ions in the body.

Conclusion: The Ubiquitous Role of Ions

In summary, atoms that gain or lose electrons are known as ions, and their formation is driven by the pursuit of a stable electron configuration. The electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions leads to ionic bonding and the formation of ionic compounds with distinct properties. Ions play a fundamental role in chemistry, biology, and various technological applications, making their understanding essential across diverse scientific disciplines and in everyday life. The wide-ranging influence of these charged particles underscores their importance in shaping the world around us.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Fraction For 0 85

Mar 28, 2025

-

Is The Elbow Proximal To The Shoulder

Mar 28, 2025

-

Is Evaporation A Chemical Or Physical Change

Mar 28, 2025

-

Which Is More Dense Oceanic Or Continental Crust

Mar 28, 2025

-

Classify These Orbital Descriptions By Type

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Atoms That Gain Or Lose Electrons Are Known As . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.