Why Are The Noble Gases Unreactive

listenit

Mar 24, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Why Are the Noble Gases Unreactive? A Deep Dive into Inertness

The noble gases, also known as inert gases, occupy Group 18 of the periodic table. Their remarkable unreactivity is a cornerstone of their identity, shaping their applications and scientific significance. This characteristic, however, isn't simply a matter of chance; it stems from a unique electronic configuration that dictates their chemical behavior. Understanding this fundamental property requires delving into the intricacies of atomic structure and chemical bonding.

The Octet Rule: The Foundation of Noble Gas Inertness

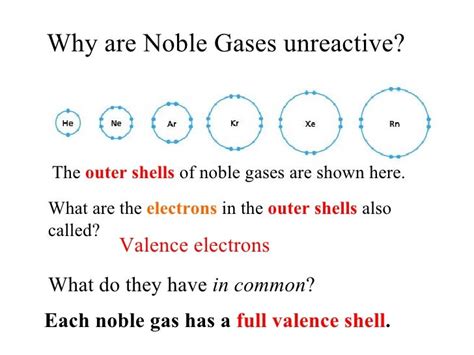

The key to understanding the noble gases' unreactivity lies in the octet rule. This rule states that atoms tend to gain, lose, or share electrons in order to achieve a stable configuration of eight electrons in their outermost electron shell, also known as the valence shell. This stable configuration mirrors that of the noble gases, providing exceptional stability and minimal reactivity.

Stable Electron Configurations: A Closer Look

Noble gases possess a full valence shell of electrons. Helium, being the smallest and lightest noble gas, has a full valence shell with two electrons (1s²). All other noble gases (neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and radon) achieve a full octet (eight electrons) in their outermost shell. This complete electron shell renders them exceptionally stable, meaning they have little tendency to participate in chemical reactions. They have no inherent "need" to gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve a more stable state – they already are in the most stable state possible.

Ionization Energy and Electron Affinity: Quantifying Inertness

The remarkable stability of noble gases is reflected in their extremely high ionization energies and very low electron affinities.

High Ionization Energy: The Difficulty of Removing Electrons

Ionization energy is the energy required to remove an electron from a neutral atom. Noble gases possess exceptionally high ionization energies because removing an electron from their already stable, full valence shell requires a significant input of energy. The strong attraction between the positively charged nucleus and the negatively charged electrons in the full valence shell makes it energetically unfavorable to remove an electron.

Low Electron Affinity: The Unwillingness to Accept Electrons

Electron affinity refers to the energy change that occurs when an atom gains an electron. Noble gases exhibit very low electron affinities. Adding an electron to an already full valence shell would require forcing it into a higher energy level, which is energetically unfavorable. The added electron would experience significant repulsion from the existing electrons in the full valence shell, destabilizing the atom rather than stabilizing it.

Van der Waals Forces: Weak Interactions in Noble Gases

While noble gases are largely unreactive, they are not entirely devoid of interatomic forces. They exhibit weak Van der Waals forces, specifically London Dispersion Forces, which arise from temporary, instantaneous dipoles in the electron clouds of atoms. These forces are significantly weaker than the covalent or ionic bonds involved in chemical reactions. The weakness of these forces explains why noble gases exist as monatomic gases at standard temperature and pressure. They do not form stable molecules with themselves or other elements because the energy gain from forming a bond is far outweighed by the energy required to disrupt the stable electronic configuration.

Exceptions to the Rule: The Reactivity of Xenon and Radon

While generally considered unreactive, some heavier noble gases, particularly xenon and radon, can form compounds under specific conditions. Their larger atomic size and increased number of electrons lead to a slightly weaker hold of the nucleus on the outermost electrons. This makes it marginally easier (though still very challenging) to perturb their stable electronic configuration.

Xenon Compounds: A Notable Exception

Xenon, with its relatively large atomic size, can form compounds with highly electronegative elements like fluorine and oxygen under extreme conditions, often involving high pressures and temperatures. These compounds are mostly fluorides and oxides, and their formation is still a testament to the remarkable stability of noble gases, as it requires significant energy input to overcome their inherent inertness. The formation of these compounds highlights the limitations of the simplistic octet rule.

Radon's Reactivity: Even Rarer Compounds

Radon, even heavier than xenon, has shown even greater potential for forming compounds. However, its radioactivity makes studying its chemistry significantly challenging and dangerous. Therefore, far fewer radon compounds have been characterized compared to xenon compounds. The extremely short half-life of radon isotopes adds another layer of difficulty in studying its chemical behaviour.

Applications of Noble Gases: Leveraging Inertness

The inertness of noble gases is precisely what makes them invaluable in various applications:

Argon in Welding and Lighting: Shielding from Oxidation

Argon's inertness makes it an ideal shielding gas in welding processes. It prevents the oxidation of molten metal, ensuring high-quality welds. Argon's inertness also protects the filament in incandescent light bulbs from oxidation, extending their lifespan.

Helium in Balloons and Scientific Instrumentation: Low Density and Inertness

Helium's low density and inertness make it suitable for inflating balloons and airships. It's also widely used in scientific instruments, such as gas chromatographs and mass spectrometers, due to its non-reactivity and ability to act as a carrier gas.

Neon in Lighting: Characteristic Glow

Neon's characteristic glow when excited electrically makes it a popular choice for signage and decorative lighting.

Krypton and Xenon in Specialized Applications: High-Intensity Lighting and Lasers

Krypton and xenon are used in high-intensity lighting applications and lasers, benefiting from their unique spectral properties and inertness.

Medical Applications: Contrast Agents and Anesthesia

Some noble gases find applications in medicine. For example, Xenon is used as an anesthetic agent and in medical imaging as a contrast agent due to its inert and non-toxic nature.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Noble Gas Inertness

The exceptional unreactivity of noble gases is a direct consequence of their stable electronic configurations, high ionization energies, and low electron affinities. This fundamental property shapes their chemical behavior, influencing their existence as monatomic gases and underpinning their widespread applications. While exceptions exist with heavier noble gases like xenon and radon forming a limited number of compounds under stringent conditions, these exceptions only reinforce the general rule of noble gas inertness. The remarkable stability of these elements continues to inspire scientific research and drive innovation across various fields, further highlighting the enduring significance of their unique chemical nature.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Gcf Of 27 And 36

Mar 26, 2025

-

How Many Fahrenheit Equals 1 Celsius

Mar 26, 2025

-

Freezing Point Of Water In K

Mar 26, 2025

-

What Is The Highest Common Factor Of 12 And 15

Mar 26, 2025

-

Find The Differential Of The Function

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Why Are The Noble Gases Unreactive . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.