Which Earth Layer Is The Thinnest

listenit

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Which Earth Layer is the Thinnest? Exploring the Earth's Composition

The Earth, our vibrant and dynamic home, is a complex system composed of several distinct layers, each with unique characteristics and properties. Understanding the structure of our planet is crucial for comprehending various geological processes, from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to the movement of tectonic plates. While the Earth's overall structure is relatively well-known, a common question arises: which layer is the thinnest? The answer, as we will explore, isn't as straightforward as it might seem, and depends on how we define "thinness."

Unveiling the Earth's Layered Structure

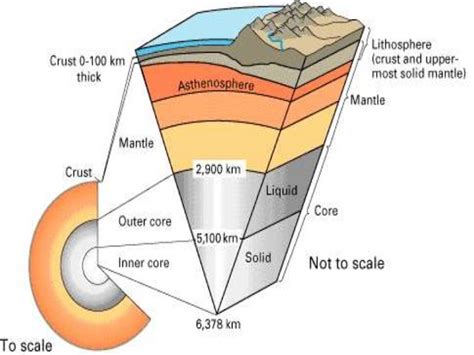

Before diving into the specifics of thickness, let's review the major layers of the Earth:

- Crust: This is the outermost solid shell, the layer we interact with directly. It's relatively thin compared to the other layers.

- Mantle: A thick, mostly solid layer located beneath the crust, extending down to a depth of about 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles).

- Outer Core: A liquid layer composed primarily of iron and nickel, responsible for generating the Earth's magnetic field.

- Inner Core: A solid sphere at the Earth's center, also primarily iron and nickel, but under immense pressure that keeps it solid despite its high temperature.

The Crust: A Thin and Fragile Shell

The Earth's crust is undeniably the thinnest of the main layers. It’s significantly less dense than the mantle, composed largely of silicate rocks. However, the crust's thickness isn't uniform across the globe. There are two distinct types:

-

Oceanic Crust: Found under the oceans, this type of crust is considerably thinner, averaging only about 5 to 10 kilometers (3 to 6 miles) in thickness. It's primarily composed of basalt, a dark-colored, dense igneous rock. The oceanic crust is consistently the thinnest layer of the Earth.

-

Continental Crust: Forming the continents, this type of crust is significantly thicker, ranging from 30 to 70 kilometers (19 to 43 miles) in thickness. It's more diverse in composition than oceanic crust, with granitic rocks being prominent. While thicker than oceanic crust, it's still relatively thin compared to the mantle.

Why is the Oceanic Crust So Thin?

The contrasting thicknesses of oceanic and continental crust are directly linked to their formation processes and the dynamics of plate tectonics. Oceanic crust is constantly being created at mid-ocean ridges, where tectonic plates diverge. Magma rises from the mantle, cools, and solidifies, forming new oceanic crust. This process is ongoing, leading to the relatively thin and young nature of oceanic crust. As older oceanic crust moves away from the ridge, it eventually subducts, or sinks back into the mantle, at convergent plate boundaries. This continuous cycle of creation and destruction keeps the oceanic crust relatively thin.

Continental crust, on the other hand, is much older and more stable. It's less prone to subduction and has undergone multiple cycles of formation and reworking throughout Earth's history. This contributes to its greater thickness and diversity in composition.

Beyond the Major Layers: The Lithosphere and Asthenosphere

While the crust is undoubtedly the thinnest major layer, the concept of "thinness" becomes more nuanced when considering the lithosphere and asthenosphere. These layers aren't defined by chemical composition but rather by their physical properties:

-

Lithosphere: This rigid outermost layer encompasses both the crust and the uppermost part of the mantle. Its thickness varies significantly, ranging from about 50 to 250 kilometers (31 to 155 miles). The lithosphere is broken into numerous tectonic plates that move and interact, causing earthquakes and volcanic activity.

-

Asthenosphere: Located beneath the lithosphere, this is a relatively weak and ductile layer of the upper mantle. It's characterized by its ability to flow slowly over geological timescales, allowing the tectonic plates to move above it.

The Lithosphere: A Composite Layer and its Thickness Variations

The lithosphere, being a composite layer including the crust, can be considered thinner under the oceans and thicker under the continents. Underneath the oceanic crust, the lithosphere is relatively thin, typically around 50-100 kilometers (31-62 miles), due to the relatively cool and rigid nature of the oceanic crust itself. This contributes to its brittle and easily fractured nature, leading to frequent seismic events at mid-ocean ridges. The lithosphere, however, thickens significantly under the continents, reaching thicknesses of 150-250 kilometers (93-155 miles) or even more. This increase is caused by the combination of thick continental crust and the cooler, denser mantle rock beneath. The older and colder the continental lithosphere becomes, the thicker it grows. This increased thickness explains the stability of the continents, their resistance to subduction, and the rarity of large-scale volcanism compared to oceanic regions.

Considering "Thinness" in Different Contexts

The question of which Earth layer is thinnest depends heavily on the context. If we consider the major compositional layers (crust, mantle, outer core, inner core), then the oceanic crust is undoubtedly the thinnest. However, if we broaden our perspective to include mechanical layers like the lithosphere and asthenosphere, the definition of "thinness" becomes more complex and relative to location (oceanic vs. continental).

The Importance of Understanding Earth's Layers

Understanding the Earth's layered structure and the relative thicknesses of its components is crucial for numerous reasons:

-

Plate Tectonics: The interaction of tectonic plates, rooted in the structure and dynamics of the lithosphere and asthenosphere, drives earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, mountain building, and the formation of ocean basins.

-

Resource Exploration: Knowledge of the different layers helps in locating and extracting valuable resources like minerals and fossil fuels.

-

Predicting Natural Hazards: Understanding the structure and behavior of the Earth's layers is essential for predicting and mitigating natural hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

-

Climate Change: The Earth's interior plays a significant role in long-term climate regulation through the release of heat and gases.

-

Planetary Science: Studying the Earth's layered structure helps us understand the formation and evolution of other planets and celestial bodies in our solar system and beyond.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Answer

In conclusion, while the oceanic crust is the thinnest major compositional layer of the Earth, the question of "thinnest" becomes more nuanced when considering mechanical layers like the lithosphere. The thickness of both compositional and mechanical layers varies considerably depending on location, age, and geological processes. This complexity highlights the intricate and dynamic nature of our planet and the importance of continued research to fully understand its structure and evolution. Appreciating the subtle differences in thickness and the implications for various geological processes is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of our Earth. The ongoing exploration of our planet's internal structure provides ongoing answers and new questions, reinforcing the exciting and dynamic field of geophysics.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Find The Domain Of F O G

Mar 17, 2025

-

Amino Acids Are The Monomers For

Mar 17, 2025

-

Why Cant Ions Pass Through The Membrane

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 170 Degrees C In Fahrenheit

Mar 17, 2025

-

175 Of What Number Is 42

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Earth Layer Is The Thinnest . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.