What Particles Orbit Around The Nucleus

listenit

Mar 18, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

What Particles Orbit Around the Nucleus? A Deep Dive into Atomic Structure

Understanding what particles orbit the nucleus is fundamental to grasping the nature of matter itself. While the simple answer is "electrons," the reality is far richer and more complex. This article delves into the intricacies of atomic structure, exploring the behavior of electrons and the forces that govern their orbital paths. We'll also touch upon the nuances of quantum mechanics and how it refines our understanding of this fundamental aspect of physics.

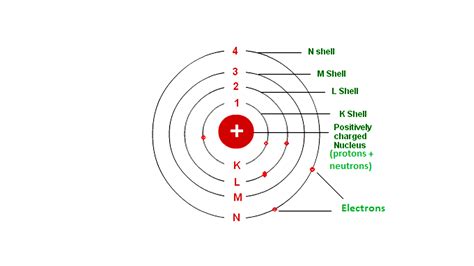

The Bohr Model: A Simplified Introduction

The most basic understanding of atomic structure comes from the Bohr model, a simplified representation that depicts electrons orbiting the nucleus in distinct energy levels or shells. This model, while outdated in its complete accuracy, provides a useful starting point.

Electrons: The Fundamental Orbital Particles

In the Bohr model, electrons, negatively charged subatomic particles, are depicted orbiting the nucleus in specific circular paths. The number of electrons in an atom dictates its chemical properties and its interactions with other atoms. The closer an electron is to the nucleus, the stronger the attractive force between the positively charged nucleus and the negatively charged electron. This attraction is crucial for maintaining the atom's structure.

Limitations of the Bohr Model

The Bohr model, while helpful for visualization, fails to explain several crucial aspects of atomic behavior. It doesn't accurately predict the behavior of atoms with many electrons, nor does it account for the wave-like nature of electrons. It doesn't explain the fine structure of spectral lines observed in atomic emission and absorption spectra. These shortcomings led to the development of more sophisticated models.

The Quantum Mechanical Model: A More Accurate Representation

The quantum mechanical model provides a far more accurate description of atomic structure. It replaces the simplistic circular orbits of the Bohr model with probability distributions describing the likelihood of finding an electron at a particular location around the nucleus.

Orbitals: Regions of Electron Probability

Instead of defined orbits, the quantum mechanical model describes electron behavior using atomic orbitals. These orbitals are regions of space around the nucleus where there is a high probability of finding an electron. They are not fixed paths, but rather three-dimensional regions that describe the electron's probable location.

Quantum Numbers: Defining Electron States

The state of an electron within an atom is described by four quantum numbers:

-

Principal Quantum Number (n): This number determines the energy level of the electron and the size of the orbital. It can have integer values (1, 2, 3, ...). Higher values of n indicate higher energy levels and larger orbitals.

-

Azimuthal Quantum Number (l): This number specifies the shape of the orbital and can have integer values from 0 to n - 1. l = 0 corresponds to an s orbital (spherical), l = 1 to a p orbital (dumbbell-shaped), l = 2 to a d orbital (more complex shapes), and so on.

-

Magnetic Quantum Number (ml): This number describes the orientation of the orbital in space. It can have integer values from -l to +l, including 0. For example, a p orbital (l = 1) can have three possible orientations (ml = -1, 0, +1).

-

Spin Quantum Number (ms): This number describes the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron, often referred to as its "spin." It can have only two values: +1/2 or -1/2, representing "spin up" and "spin down," respectively. This is crucial for understanding electron configurations and chemical bonding.

The Nucleus: The Central Core

While electrons are the particles that orbit the nucleus, it's important to understand the nucleus itself. The nucleus is the dense central region of an atom, containing two types of particles:

Protons: Positively Charged Particles

Protons are positively charged subatomic particles. The number of protons in an atom's nucleus determines its atomic number and defines the element. For example, an atom with one proton is hydrogen, an atom with six protons is carbon, and so on. Protons contribute significantly to the mass of the atom.

Neutrons: Neutral Particles

Neutrons are electrically neutral particles, meaning they carry no charge. They reside in the nucleus alongside protons and contribute to the atom's mass. The number of neutrons in an atom's nucleus can vary, resulting in different isotopes of the same element. Isotopes have the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons.

Beyond Electrons: Other Subatomic Particles

While electrons are the primary particles orbiting the nucleus, other subatomic particles exist within the atom, though they don't directly orbit in the same way electrons do. These particles are primarily found within the nucleus and contribute to the atom's overall structure and properties. These include:

-

Quarks: Protons and neutrons are not fundamental particles. They are composed of smaller particles called quarks. There are six types of quarks (up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom), and protons and neutrons are each made up of three quarks.

-

Gluons: Gluons are the force-carrying particles responsible for the strong nuclear force, which binds quarks together within protons and neutrons.

The Forces Governing Orbital Motion

The motion of electrons around the nucleus is governed by two fundamental forces:

The Electromagnetic Force: Attraction Between Opposite Charges

The electromagnetic force is the primary force responsible for keeping electrons in the vicinity of the nucleus. The positive charge of the protons in the nucleus attracts the negatively charged electrons, preventing them from flying off. This force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. The closer an electron is to the nucleus, the stronger the attractive force.

The Strong Nuclear Force: Binding Protons and Neutrons

The strong nuclear force is a much stronger force than the electromagnetic force, but it acts only over very short distances—within the nucleus itself. This force is responsible for binding protons and neutrons together, overcoming the electromagnetic repulsion between the positively charged protons. Without the strong nuclear force, the nucleus would simply fly apart.

Quantum Mechanics and Electron Behavior

The behavior of electrons is governed by the principles of quantum mechanics. This means that electrons don't behave like tiny planets orbiting the sun. Instead, their behavior is probabilistic, and their location can only be described in terms of probabilities.

Wave-Particle Duality: Electrons as Waves

Electrons exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties, a concept known as wave-particle duality. This means that electrons can be described as both particles with mass and charge, and as waves with a wavelength related to their momentum. This wave-like nature is crucial for understanding the shapes of atomic orbitals.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle: Limitations on Knowledge

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle states that it's impossible to simultaneously know both the position and momentum of an electron with perfect accuracy. The more precisely we know the electron's position, the less precisely we know its momentum, and vice versa. This principle is a fundamental limitation on our ability to fully predict the behavior of electrons.

Electron Shells and Subshells: Organization of Electrons

Electrons are arranged in shells and subshells around the nucleus according to their energy levels and quantum numbers. Electrons in the same shell have approximately the same energy, while electrons in the same subshell have the same energy and shape of orbital. The filling of these shells and subshells determines the chemical properties of an atom. This arrangement is dictated by the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers.

Conclusion: A Complex and Fascinating System

The particles that orbit the nucleus are primarily electrons, but their behavior is far more intricate than a simple planetary model might suggest. The quantum mechanical model provides a far more accurate description, illustrating the probabilistic nature of electron location and the importance of quantum numbers in defining their states. The electromagnetic and strong nuclear forces play crucial roles in maintaining the atom's structure, and the wave-particle duality of electrons further underscores the complexities of the atomic world. Understanding these fundamental concepts is key to comprehending the behavior of matter at the atomic level and beyond. Further exploration of quantum field theory and particle physics can illuminate even deeper layers of this fascinating subject.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Power Series For Ln 1 X

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Are The Five Properties Of A Mineral

Mar 18, 2025

-

7 Out Of 10 As A Percentage

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is The Gcf Of 12 And 15

Mar 18, 2025

-

How To Measure Out Amount Of Acid

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Particles Orbit Around The Nucleus . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.