What Are The Five Properties Of A Mineral

listenit

Mar 18, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Are the Five Properties of a Mineral? A Comprehensive Guide

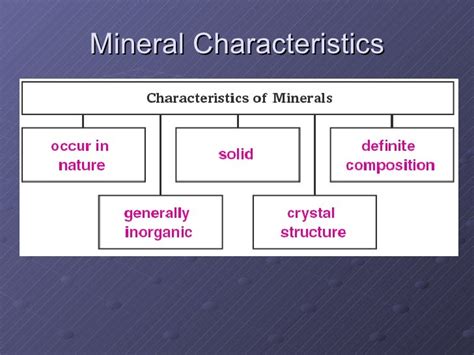

Minerals are the fundamental building blocks of rocks and the Earth's crust. Understanding their properties is crucial for geologists, mineralogists, and anyone interested in the natural world. But what exactly defines a mineral, and what are the five key properties used to identify them? This comprehensive guide dives deep into the five defining properties of minerals: naturally occurring, inorganic, solid, definite chemical composition, and ordered atomic arrangement. We'll explore each property in detail, providing examples and clarifying common misconceptions.

1. Naturally Occurring

This property might seem straightforward, but it's crucial for distinguishing minerals from human-made materials. A mineral must be formed by natural geological processes, excluding any human intervention. This means it can't be synthesized in a lab or created artificially.

Understanding Natural Geological Processes

Natural geological processes encompass a wide range of phenomena, including:

- Magmatic processes: Crystallization of molten rock (magma) as it cools. Examples include the formation of feldspar and quartz in granite.

- Sedimentary processes: Precipitation from solution or accumulation of fragments of pre-existing rocks and minerals. Halite (rock salt) is a prime example formed through evaporation of seawater.

- Metamorphic processes: Transformation of existing rocks and minerals due to heat, pressure, or chemical reactions. Garnet, a common metamorphic mineral, forms under high-pressure conditions.

- Hydrothermal processes: Precipitation of minerals from hot, aqueous solutions. Many metallic ore deposits form through hydrothermal processes.

Distinguishing Minerals from Synthetics

Consider diamonds. Naturally occurring diamonds formed under immense pressure deep within the Earth's mantle. However, lab-grown diamonds share the same chemical composition and crystal structure. The key difference lies in their origin; lab-grown diamonds are not considered minerals because they aren't formed by natural geological processes. Similarly, synthetic rubies, while possessing the same chemical makeup as natural rubies, are not minerals due to their artificial origin.

2. Inorganic

The inorganic nature of minerals distinguishes them from organic compounds, which are typically associated with living organisms or their byproducts. Inorganic compounds lack the complex carbon-based structures that characterize organic molecules.

Defining Inorganic

The term "inorganic" in the context of mineralogy indicates the absence of carbon-hydrogen bonds, which are the hallmark of organic molecules. While some minerals might contain carbon (like calcite, CaCO₃), they generally lack the complex carbon chains and rings characteristic of organic compounds. The formation mechanisms of inorganic minerals are also fundamentally different, usually involving geological processes rather than biological ones.

Exceptions and Considerations

While the distinction between organic and inorganic is generally clear-cut, there are some gray areas. For instance, some minerals form through the activity of organisms (biomineralization). Shells and bones, primarily composed of calcite and apatite respectively, are good examples. These minerals are considered inorganic despite their biological origin because the formation process involves inorganic precipitation from solution, governed by physicochemical processes, rather than the direct synthesis by living organisms.

3. Solid

Mineralogy defines minerals as solid substances. This means they maintain a definite shape and volume under normal conditions. Liquids and gases, lacking fixed shapes and volumes, do not qualify as minerals. This seemingly simple criterion is crucial for classification.

Crystalline Structure and Solid State

The solid state of a mineral is intrinsically linked to its ordered atomic arrangement (discussed in detail later). Atoms in a mineral are bound together in a highly organized, three-dimensional structure, forming a crystal lattice. This regular arrangement gives minerals their characteristic hardness, cleavage, and other physical properties.

Exceptions and Special Cases

While the solid-state criterion is generally straightforward, certain minerals can exhibit polymorphs – minerals with the same chemical composition but different crystal structures, sometimes existing in different states. For example, graphite and diamond are both composed entirely of carbon but have vastly different physical properties due to their different crystal structures. However, both are considered minerals because both, under normal conditions, are solid.

4. Definite Chemical Composition

Minerals have a specific chemical formula, representing the fixed ratios of elements present in their structure. While some variation can occur due to substitution of atoms, the overall composition remains fairly consistent within a given mineral species.

Chemical Formulae and Variations

The chemical formula provides a precise representation of the elements and their ratios in a mineral. For example, quartz has the formula SiO₂, indicating a 1:2 ratio of silicon (Si) to oxygen (O) atoms. However, some degree of substitution can occur. In some cases, minor elements can substitute for major elements in the crystal lattice, leading to variations in the chemical composition. This is known as isomorphic substitution and contributes to the diversity of mineral compositions.

Understanding Isomorphic Substitution

Isomorphic substitution is a significant concept in mineralogy. It occurs when atoms of similar size and charge replace each other in the crystal lattice without altering the overall crystal structure. For example, in the olivine group, iron (Fe) can substitute for magnesium (Mg), resulting in a range of compositions from pure forsterite (Mg₂SiO₄) to pure fayalite (Fe₂SiO₄). This substitution doesn’t change the mineral's classification (it remains an olivine), but it affects its physical properties, such as color and density.

5. Ordered Atomic Arrangement

This refers to the highly organized, three-dimensional structure of atoms within a mineral. Atoms are arranged in a repeating, regular pattern called a crystal lattice. This ordered arrangement dictates many of the mineral's physical and chemical properties.

Crystal Lattices and Crystal Systems

The crystal lattice is the fundamental unit of a mineral's structure. It determines the symmetry of the crystal, its cleavage planes, and its overall shape. Minerals are categorized into seven crystal systems based on the symmetry of their lattices: cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, hexagonal, and trigonal.

Amorphous Materials and Minerals

While most minerals exhibit a highly ordered atomic arrangement, some exceptions exist. Amorphous materials lack a long-range ordered structure. Opal, for instance, is a mineraloid – a naturally occurring inorganic solid lacking the ordered atomic arrangement characteristic of minerals. While it fits most other criteria for being a mineral, its lack of crystalline structure disqualifies it from being classified as a true mineral.

Conclusion: Identifying Minerals

The five properties—naturally occurring, inorganic, solid, definite chemical composition, and ordered atomic arrangement—provide a robust framework for classifying and identifying minerals. While each property can be investigated through various tests and observations, understanding their interplay is crucial for accurate mineral identification. The combination of these properties gives each mineral its unique identity and helps explain its behavior within geological systems. This knowledge is fundamental to a deeper appreciation of the Earth’s composition and the processes shaping our planet. By understanding these fundamental properties, we can unlock a vast world of geological wonders and scientific discovery.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Greatest Common Factor Of 90 And 36

Mar 18, 2025

-

45 Of What Number Is 27

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between A Solute And Solvent

Mar 18, 2025

-

Where Is The Trunk On The Body

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is 1 3rd Of 18

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Are The Five Properties Of A Mineral . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.