How Many Nitrogen Bases Make A Codon

listenit

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

How Many Nitrogenous Bases Make a Codon? Decoding the Language of Life

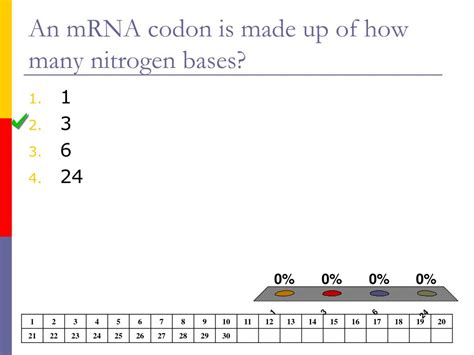

The fundamental unit of heredity, the gene, is encoded within the intricate structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This molecule, the blueprint of life, uses a specific code to dictate the synthesis of proteins, the workhorses of the cell. Understanding this code hinges on grasping the concept of the codon – the cornerstone of genetic translation. So, how many nitrogenous bases make a codon? The answer, simply put, is three. However, this seemingly straightforward response opens a door to a wealth of fascinating biological detail. This article will delve deep into the world of codons, exploring their structure, function, and significance in the broader context of molecular biology.

Understanding the Players: Nitrogenous Bases and Codons

Before we delve into the specifics of codon composition, let's define the key players involved. DNA is composed of a double helix structure formed by two strands of nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of three components:

- A deoxyribose sugar: This five-carbon sugar forms the backbone of the DNA molecule.

- A phosphate group: This links the sugar molecules together, creating the DNA strand.

- A nitrogenous base: This is the information-carrying component of the nucleotide. There are four types:

- Adenine (A)

- Guanine (G)

- Cytosine (C)

- Thymine (T)

These nitrogenous bases pair specifically: A with T, and G with C. This base pairing is crucial for DNA replication and transcription.

Now, let's move to the codon. A codon is a sequence of three consecutive nitrogenous bases in a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule that specifies a particular amino acid during protein synthesis. It's the fundamental unit of the genetic code. The mRNA is a single-stranded copy of a gene, transcribed from DNA. Instead of thymine (T), mRNA uses uracil (U). Therefore, the bases in mRNA are A, U, G, and C.

The Genetic Code: A Triplet Code

The genetic code is essentially a dictionary that translates the sequence of mRNA codons into the sequence of amino acids that make up a protein. Since there are four bases (A, U, G, C) and each codon is composed of three bases, there are 4³ = 64 possible codons. This is more than enough to code for the 20 amino acids commonly found in proteins. This redundancy is a crucial aspect of the code's robustness, providing protection against mutations.

The Redundancy of the Genetic Code: Why More Than One Codon Can Code for the Same Amino Acid

The fact that there are 64 codons but only 20 amino acids means that multiple codons can code for the same amino acid. This is called codon degeneracy or redundancy. For example, the amino acid leucine is encoded by six different codons: UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, and CUG. This redundancy offers several advantages:

- Protection against mutations: A change in a single base (a point mutation) might not alter the amino acid sequence if the resulting codon still codes for the same amino acid. This minimizes the impact of errors during DNA replication or transcription.

- Error correction: The redundancy helps to correct errors during translation.

- Evolutionary flexibility: The degeneracy allows for variations in the genetic code without affecting the protein's functionality.

Start and Stop Codons: Initiating and Terminating Protein Synthesis

Within the 64 codons, three are special: they don't code for amino acids but instead signal the start and stop of protein synthesis.

- Start codon (AUG): This codon signals the beginning of protein synthesis. It also codes for the amino acid methionine.

- Stop codons (UAA, UAG, UGA): These codons signal the end of protein synthesis. They don't code for any amino acid and cause the ribosome to release the newly synthesized polypeptide chain.

The Process of Translation: From Codons to Proteins

The information encoded in the mRNA codons is translated into a protein sequence through a complex process involving ribosomes, transfer RNA (tRNA), and various protein factors.

-

Initiation: The ribosome binds to the mRNA molecule and identifies the start codon (AUG). A tRNA molecule carrying methionine binds to the start codon.

-

Elongation: The ribosome moves along the mRNA molecule, reading each codon sequentially. For each codon, a specific tRNA molecule carrying the corresponding amino acid binds to the ribosome. The amino acids are then linked together through peptide bonds, forming a polypeptide chain.

-

Termination: When a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) is encountered, the ribosome releases the completed polypeptide chain, which then folds into a functional protein.

Mutations and Their Impact on Codon Sequences

Mutations are changes in the DNA sequence that can alter the codon sequence. These changes can have various consequences, ranging from no effect to severe phenotypic alterations. There are several types of mutations:

-

Point mutations: These involve a change in a single base. They can be:

- Silent mutations: The altered codon still codes for the same amino acid. This is possible due to codon degeneracy.

- Missense mutations: The altered codon codes for a different amino acid. The effect of this can vary widely depending on the nature of the amino acid change and its location in the protein.

- Nonsense mutations: The altered codon becomes a stop codon, resulting in premature termination of protein synthesis. This often leads to non-functional or truncated proteins.

-

Frameshift mutations: These involve the insertion or deletion of one or more bases, altering the reading frame of the codons. This results in a completely different amino acid sequence downstream from the mutation, often leading to a non-functional protein.

Codon Usage Bias: Not All Codons Are Created Equal

While the genetic code is universal (the same codons code for the same amino acids in almost all organisms), there is variation in how frequently different codons are used to encode a particular amino acid within a given genome. This phenomenon is known as codon usage bias. Certain codons are preferred over others, even though they code for the same amino acid. The reasons for codon usage bias are complex and likely involve factors such as:

- tRNA availability: Organisms may have a higher abundance of tRNAs for certain codons.

- mRNA secondary structure: The frequency of certain codons may influence the mRNA's secondary structure and translational efficiency.

- Gene expression levels: Highly expressed genes often use codons that are optimally translated.

Conclusion: The Codon – A Cornerstone of Life's Code

The simple answer, three nitrogenous bases, belies the profound complexity of the codon. Understanding the structure, function, and nuances of codons – their redundancy, the start and stop signals, the impact of mutations, and codon usage bias – provides a fundamental understanding of the intricate mechanism of protein synthesis and the genetic code that underpins all life. The 64 codons are not merely a sequence of bases; they are the words that make up the language of life, directing the construction of the proteins that drive biological processes and define the characteristics of every organism. Further research into these intricate details continues to reveal new insights into the elegance and precision of the biological machinery that makes life possible.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

8x 4 4x 3 4 6x 4 4

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Do The Arrows On A Food Chain Represent

Mar 15, 2025

-

Is Salt An Element Compound Or Mixture

Mar 15, 2025

-

How Many Millimeters Are In One Meter

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is 1 2 3 8

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Many Nitrogen Bases Make A Codon . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.