How Does Igneous Rock Turn Into Sedimentary

listenit

Mar 23, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

How Igneous Rock Turns into Sedimentary Rock: A Comprehensive Guide

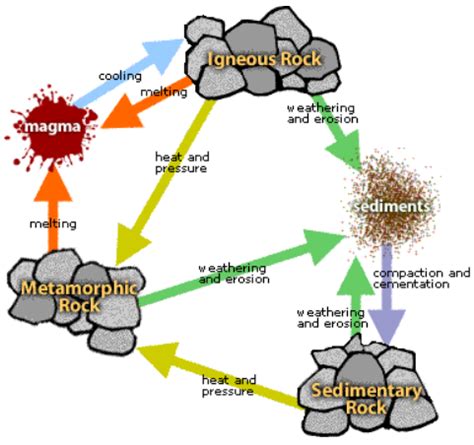

The Earth's crust is a dynamic tapestry woven from three primary rock types: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. Understanding the processes that transform one rock type into another is fundamental to grasping the planet's geological history and the constant cycle of rock formation and alteration. This article delves into the fascinating journey of igneous rock's metamorphosis into sedimentary rock, a process spanning millions of years and involving several crucial steps.

The Starting Point: Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks, formed from the cooling and solidification of molten magma or lava, represent the initial stage in our transformation story. These rocks, whether intrusive (formed beneath the Earth's surface) like granite or extrusive (formed on the surface) like basalt, are incredibly diverse in their mineral composition and texture. Their journey to becoming sedimentary rocks begins with the relentless forces of weathering and erosion.

Weathering: The Break Down

Weathering, the disintegration and decomposition of rocks at or near the Earth's surface, is the first critical step. Two primary types of weathering work in tandem to break down igneous rocks:

-

Physical Weathering: This involves the mechanical breakdown of rocks without altering their chemical composition. Processes like frost wedging (water freezing and expanding in cracks), thermal expansion and contraction (temperature fluctuations causing stress), and abrasion (rocks grinding against each other) contribute to the fragmentation of igneous rocks into smaller pieces. Imagine a massive granite outcrop gradually crumbling into smaller and smaller fragments under the relentless assault of these physical forces.

-

Chemical Weathering: This involves the alteration of the chemical composition of rocks through reactions with water, air, and dissolved substances. Hydrolysis (water reacting with minerals), oxidation (reaction with oxygen), and carbonation (reaction with carbonic acid) are key chemical processes. These reactions weaken the mineral bonds within the igneous rock, making it more susceptible to further breakdown. For instance, feldspar, a common mineral in many igneous rocks, readily weathers to form clay minerals.

The intensity and type of weathering depend on various factors, including climate (temperature, rainfall, and freeze-thaw cycles), the composition of the igneous rock, and the presence of vegetation. A hot, humid climate accelerates chemical weathering, while a cold, dry climate may favor physical weathering.

Erosion: The Transportation

Once weathered into smaller particles, the fragments of igneous rock, now classified as sediment, are transported away from their source by various erosional agents:

-

Water: Rivers, streams, and ocean currents are powerful agents of erosion, carrying sediment downstream or offshore. The size and type of sediment transported depend on the velocity and energy of the water flow. Faster-flowing water can carry larger, heavier particles, while slower-flowing water transports finer sediments.

-

Wind: Wind erosion is particularly effective in arid and semi-arid regions. Strong winds can lift and transport fine sand and dust particles over vast distances. Think of the vast sand dunes of deserts – these are often composed of weathered and eroded particles from a variety of rock sources, including igneous rocks.

-

Ice: Glaciers are incredibly powerful agents of erosion, capable of transporting enormous quantities of sediment. As glaciers move, they pick up and incorporate rock fragments, which are then deposited when the glacier melts. The characteristic unsorted nature of glacial deposits reflects this powerful erosional force.

-

Gravity: Gravity plays a crucial role in mass wasting events like landslides and rockfalls, which rapidly transport large volumes of sediment downslope.

The transportation process further breaks down the sediment, rounding the edges and sorting the particles by size. This sorting process is critical in determining the texture of the eventual sedimentary rock.

Lithification: The Transformation

The final stage in the transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is lithification, which involves the consolidation and hardening of sediment into solid rock. This process occurs over considerable time and depth within sedimentary basins. Several key steps are involved:

-

Compaction: As layers of sediment accumulate, the weight of overlying layers compresses the underlying layers. This compaction reduces the pore space between sediment grains, squeezing out water and air. The denser packing of particles increases the rock's strength and rigidity.

-

Cementation: Dissolved minerals in groundwater precipitate within the pore spaces of the compacted sediment, acting as a natural glue that binds the particles together. Common cementing agents include calcite, silica, and iron oxides. These minerals fill the spaces between sediment grains, creating a solid, interconnected framework.

The type of cementing agent, the degree of compaction, and the size and shape of the sediment grains influence the properties of the resulting sedimentary rock.

Types of Sedimentary Rocks Derived from Igneous Protoliths

The sedimentary rocks formed from weathered and eroded igneous rocks exhibit a variety of characteristics reflecting the nature of the parent igneous rock and the processes involved in their formation. Some common examples include:

-

Sandstone: Formed from the lithification of sand-sized sediment derived from weathered igneous rocks such as granite and basalt. The grain size and composition of the sandstone will vary depending on the parent rock and the transportation process.

-

Shale: Formed from the lithification of clay-sized sediment, often resulting from the chemical weathering of feldspar minerals within igneous rocks. Shale is characterized by its fine grain size and ability to split into thin layers.

-

Conglomerate: Formed from the lithification of a mixture of large and small sediment particles, often including pebbles and cobbles derived from weathered igneous rocks. Conglomerates are characteristic of high-energy depositional environments.

-

Arkose: A type of sandstone containing a significant proportion of feldspar, indicating relatively rapid weathering and transportation from a nearby igneous source.

The specific mineral composition of the sedimentary rock will reflect the composition of the original igneous rock. For example, sedimentary rocks derived from felsic igneous rocks (rich in feldspar and quartz) will tend to have a higher silica content than sedimentary rocks derived from mafic igneous rocks (rich in iron and magnesium-rich minerals).

The Rock Cycle's Continuous Transformation

The transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is not a one-way street. It's part of the Earth's dynamic rock cycle, a continuous process involving the transformation of one rock type into another. Sedimentary rocks themselves can be subjected to further metamorphism, transforming into metamorphic rocks under intense heat and pressure. These metamorphic rocks can then melt to form new magma, eventually crystallizing into igneous rocks, completing the cycle.

Understanding the rock cycle provides insight into the age and formation of different rock formations, the distribution of minerals and resources, and the dynamic interplay of geological processes shaping our planet. The intricate details of this cycle, particularly the detailed mechanisms of weathering, erosion, and lithification, are actively researched by geologists worldwide, providing us with constantly evolving insights into the Earth's history.

Further Considerations: Factors Influencing Transformation Rates

The rate at which igneous rock transforms into sedimentary rock is influenced by several key factors, making it a highly variable process across different geological settings:

-

Climate: Arid climates tend to have slower weathering rates compared to humid climates. The abundance of water and fluctuating temperatures in humid regions promotes more rapid chemical and physical weathering.

-

Rock Composition: The mineral composition of the igneous rock dictates its susceptibility to weathering. Rocks with less resistant minerals, such as those containing olivine or pyroxene, will weather faster than those with resistant minerals like quartz.

-

Topography: Steeper slopes promote faster erosion rates, accelerating the transport of weathered material. Flatter landscapes allow for slower erosion and greater accumulation of sediment.

-

Vegetation: Plant roots can physically break down rocks and contribute organic acids that enhance chemical weathering. The presence or absence of vegetation can significantly influence weathering rates.

-

Biological Activity: Certain organisms, such as lichens and bacteria, can actively contribute to weathering through their metabolic processes. Their influence, while less pronounced on a large scale, can still be significant locally.

-

Human Activities: Human activities such as mining, deforestation, and construction can significantly accelerate erosion and weathering rates, altering natural geological processes.

Conclusion: A Journey Through Time

The transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is a testament to the Earth's immense power and the continuous cycle of creation and destruction. This process, spanning millions of years, is a fundamental aspect of geology and provides crucial insights into the planet's history. By understanding the complex interplay of weathering, erosion, and lithification, we gain a deeper appreciation for the dynamic forces shaping our world and the rich diversity of rocks that form its surface. The next time you see a sandstone cliff or a shale outcrop, remember the long and fascinating journey of the igneous rock that preceded it, transformed over millennia into the sedimentary rock we see today.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Pounds Is One Pint

Mar 24, 2025

-

Derivative Of 2 Square Root Of X

Mar 24, 2025

-

How Many Electrons Does Mercury Have

Mar 24, 2025

-

Volume Of 1 Mole Gas At Stp

Mar 24, 2025

-

How Many 1 3 Make 1 2 Cup

Mar 24, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Does Igneous Rock Turn Into Sedimentary . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.