At What Temperature Is Water At Its Densest

listenit

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

At What Temperature Is Water At Its Densest? A Deep Dive into Water's Anomalous Behavior

Water, the elixir of life, is a substance so fundamental to our existence that we often overlook its remarkable properties. One of the most intriguing and crucial of these properties is its density, and specifically, the temperature at which it achieves its maximum density. Understanding this seemingly simple question opens a door to a fascinating exploration of molecular interactions, hydrogen bonding, and the far-reaching consequences for our planet's ecosystems and climate.

The Unexpected Answer: 4°C (39.2°F)

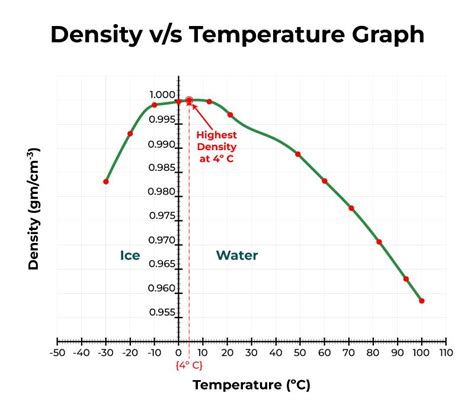

Contrary to the intuitive assumption that water's density increases steadily as it cools, water reaches its maximum density at a temperature of 4°C (39.2°F). Below this temperature, water becomes less dense, a phenomenon that has profound implications for aquatic life and global climate patterns. This anomalous behavior isn't simply a quirk of nature; it's a consequence of the unique properties of water molecules and their interactions.

The Role of Hydrogen Bonding

The key to understanding water's unusual density behavior lies in its molecular structure and the strong hydrogen bonds that form between water molecules (H₂O). Each water molecule is composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, arranged in a bent shape. The oxygen atom is more electronegative than the hydrogen atoms, meaning it attracts electrons more strongly. This creates a partial negative charge (δ-) on the oxygen and partial positive charges (δ+) on the hydrogens.

These partial charges allow water molecules to form strong hydrogen bonds with each other. Each water molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules, creating a complex, three-dimensional network. The arrangement and strength of these hydrogen bonds are critically influenced by temperature.

Density Changes with Temperature: A Detailed Explanation

At temperatures above 4°C, the kinetic energy of water molecules is relatively high. This means the molecules are moving rapidly and disrupting the ordered hydrogen bond network. As the temperature decreases, the molecules slow down, allowing for more ordered hydrogen bonding. This leads to a tighter packing of molecules and an increase in density.

However, as the temperature drops below 4°C, a remarkable shift occurs. The formation of ordered, crystalline structures, characteristic of ice, begins to dominate. In ice, the hydrogen bonds force a more open, less dense structure. This hexagonal lattice structure incorporates more space than the more disordered arrangement at 4°C, resulting in a lower density for ice compared to liquid water at 4°C. This is why ice floats on water.

The Significance of Ice Floating

The fact that ice floats is absolutely crucial for aquatic life. If ice were denser than water, it would sink to the bottom of lakes and oceans, leading to the formation of massive ice sheets that would prevent aquatic organisms from surviving during winter. The lower density of ice acts as an insulating layer, preventing further freezing and allowing life to persist beneath the icy surface.

Implications for Aquatic Ecosystems

The density anomaly of water significantly impacts the stratification and mixing of water bodies. In freshwater lakes, for instance, the density differences between water at different temperatures lead to the formation of distinct layers during seasonal temperature changes. This layering, known as thermal stratification, has profound consequences for the distribution of oxygen, nutrients, and organisms within the lake ecosystem.

During summer, a warm, less dense layer (epilimnion) forms on the surface, while a cooler, denser layer (hypolimnion) resides at the bottom. The transition zone between these layers is called the metalimnion or thermocline. This stratification can limit the mixing of oxygen and nutrients, affecting the productivity and health of the ecosystem. During autumn and spring, as water temperatures equalize, a process called lake turnover occurs, leading to thorough mixing of the water column.

In marine environments, the density anomaly also plays a crucial role in ocean currents and global heat distribution. Temperature differences in the ocean, influenced by water's density variations, drive ocean currents that transport heat and nutrients around the globe, playing a vital role in regulating the Earth's climate.

Beyond the Basic Explanation: Further Nuances

While the 4°C maximum density point is a cornerstone of understanding water's properties, the reality is more nuanced. The precise temperature of maximum density can be slightly affected by factors such as pressure and the presence of dissolved salts. At higher pressures, such as those found in the deep ocean, the temperature of maximum density shifts slightly lower.

The presence of dissolved salts, like those in seawater, also affects the density-temperature relationship. Seawater exhibits a different density profile compared to freshwater, and the temperature of maximum density is lower in seawater than in pure water. This variation is crucial for understanding oceanographic processes and climate modeling.

The Impact on Climate and Weather Patterns

The anomalous density of water has substantial implications for global climate and weather patterns. The relatively high heat capacity of water, combined with its density variations, acts as a significant buffer against rapid temperature fluctuations. Oceans absorb and release vast amounts of heat, moderating global temperatures and preventing extreme climate swings.

The density differences in water drive ocean currents, which are responsible for distributing heat around the globe. These currents, driven by a combination of temperature, salinity, and wind, influence regional climates and play a significant role in weather patterns. Changes in ocean temperatures and salinity can impact the strength and patterns of ocean currents, potentially leading to alterations in regional and global climates.

Research and Ongoing Studies

The study of water's properties, especially its density behavior, continues to be an active area of scientific research. Scientists are employing advanced techniques like molecular dynamics simulations and experimental measurements to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular interactions and their implications for various phenomena.

Research focusing on the impact of climate change on water's properties is particularly important. Rising global temperatures, changes in salinity, and melting glaciers are all expected to influence the density and circulation patterns of water bodies, potentially triggering far-reaching consequences for ecosystems and climate.

Conclusion: Water's Amazing Anomaly

The temperature at which water achieves its maximum density—4°C—is not merely a scientific curiosity; it’s a fundamental property with profound implications for life on Earth. This anomalous behavior, a direct consequence of hydrogen bonding, shapes aquatic ecosystems, influences ocean currents, and plays a crucial role in regulating our planet's climate. Further research into this remarkable property will undoubtedly continue to unveil new insights into the complex workings of our world. The seemingly simple question of "At what temperature is water at its densest?" opens a vast and fascinating exploration of water's vital role in sustaining life and shaping our planet's environment.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Flag Pole Is Supported By Two Wires

Mar 19, 2025

-

Expansion Of 1 X 1 X

Mar 19, 2025

-

Based On The Relative Bond Strengths

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Does Deforestation Affect The Water Cycle

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is 7 To The Power Of 2

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about At What Temperature Is Water At Its Densest . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.