Are Phase Changes Chemical Or Physical

listenit

Apr 02, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Are Phase Changes Chemical or Physical? A Deep Dive

Phase changes are a fundamental concept in chemistry and physics, representing transitions between the different states of matter: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. A common question that arises is whether these changes – like melting, freezing, boiling, and condensation – are chemical or physical processes. The answer, simply put, is physical. However, understanding why requires a deeper exploration of the underlying principles. This article will delve into the characteristics of phase changes, comparing them to chemical changes, and clarifying the crucial distinctions.

Understanding Physical and Chemical Changes

Before we delve into the specifics of phase changes, let's establish a clear definition of physical and chemical changes.

Physical Changes

A physical change alters the form or appearance of a substance but doesn't change its chemical composition. The molecules themselves remain the same; only their arrangement or state of motion changes. Examples include:

- Changes in state: Melting ice, boiling water, condensing steam, freezing liquids.

- Changes in shape: Cutting paper, bending a wire, crushing a can.

- Dissolving: Salt dissolving in water (though the solution is a new mixture, the salt molecules retain their identity).

Key characteristics of physical changes include:

- No new substance is formed. The chemical identity of the matter remains unchanged.

- Changes are often reversible. For instance, water can be frozen and then melted back into liquid water.

- Usually involves relatively small energy changes.

Chemical Changes

A chemical change, also known as a chemical reaction, involves the transformation of one or more substances into entirely new substances with different chemical properties. This involves the breaking and forming of chemical bonds, resulting in a change in the molecular structure. Examples include:

- Combustion: Burning wood or fuel.

- Rusting: The oxidation of iron.

- Cooking: The chemical changes that occur during baking a cake.

- Digestion: The breakdown of food into simpler molecules.

Key characteristics of chemical changes include:

- New substances are formed. The chemical identity of the matter is altered.

- Changes are often irreversible. For example, you cannot easily un-burn wood.

- Usually involves significant energy changes. Reactions can be exothermic (releasing heat) or endothermic (absorbing heat).

Phase Changes: A Detailed Look

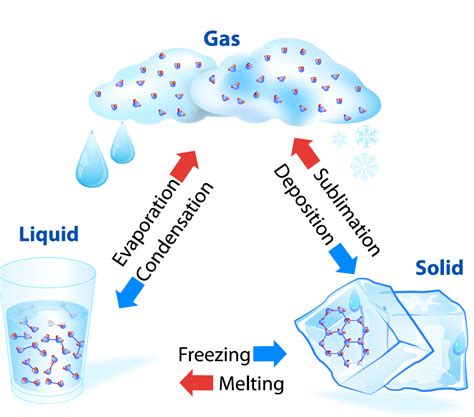

Phase changes, as mentioned earlier, are transitions between solid, liquid, gas, and plasma states. These transitions involve changes in the energy of the molecules and their interactions, leading to alterations in their arrangement and movement.

Common Phase Transitions

Let's explore some common phase transitions and how they fit within the definition of physical changes:

-

Melting (Solid to Liquid): When a solid is heated, the kinetic energy of its molecules increases. At the melting point, this energy overcomes the intermolecular forces holding the molecules in a fixed lattice structure. The molecules gain freedom of movement, transitioning to the liquid phase. No new substance is formed; it's simply water in a different physical state.

-

Freezing (Liquid to Solid): The reverse of melting, freezing occurs when a liquid is cooled. The kinetic energy decreases, and intermolecular forces become dominant, causing the molecules to arrange themselves into a regular, ordered structure characteristic of a solid. Again, the chemical composition remains unchanged.

-

Vaporization (Liquid to Gas): Vaporization encompasses both boiling and evaporation. Boiling occurs at a specific temperature (the boiling point) when the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the external pressure. Evaporation occurs at temperatures below the boiling point, with molecules escaping from the liquid's surface. In both cases, molecules gain enough kinetic energy to overcome the intermolecular forces holding them in the liquid state, transitioning to the gaseous phase. The molecules are still the same; only their arrangement and energy have changed.

-

Condensation (Gas to Liquid): Condensation is the reverse of vaporization. As a gas cools, its molecules lose kinetic energy, and intermolecular forces become significant enough to pull the molecules together, forming a liquid. No new substance is created; it's merely a change in state.

-

Sublimation (Solid to Gas): Sublimation occurs when a solid transitions directly to the gaseous phase without passing through the liquid phase (e.g., dry ice). This happens when the molecules have enough kinetic energy to overcome the intermolecular forces in the solid state and escape directly into the gas phase. The chemical composition remains unchanged throughout this process.

-

Deposition (Gas to Solid): Deposition is the opposite of sublimation. It's the direct transition from the gaseous to the solid phase without passing through the liquid phase (e.g., frost formation). This is also a physical change, involving only a change in the arrangement and energy of the molecules.

Why Phase Changes are Physical, Not Chemical

The crucial factor distinguishing phase changes from chemical changes is the absence of a change in chemical composition. In phase changes, the molecules themselves remain intact. The only changes are in their arrangement, distances between them, and the strength of intermolecular forces. No chemical bonds are broken or formed.

Imagine water (H₂O). Whether it's ice, liquid water, or steam, it's still composed of the same molecules – two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to one oxygen atom. The phase change merely alters the way these water molecules interact and are arranged.

Conversely, chemical changes involve the breaking and forming of chemical bonds, creating entirely new substances with different properties. For example, burning wood (a chemical change) transforms the cellulose and lignin in wood into carbon dioxide, water vapor, and ash—completely different substances with different chemical compositions.

Energy and Phase Changes

Phase changes are always accompanied by energy changes. The energy required or released during a phase transition is known as the latent heat. This energy is absorbed or released without changing the temperature of the substance. For example, during melting, energy is absorbed to overcome the intermolecular forces holding the solid together. During freezing, energy is released as the molecules form new bonds in the solid state. This energy transfer is a characteristic of a physical process, not a chemical one. The energy is used to change the state of the substance, not to alter its chemical identity.

Plasma: A Fourth State of Matter

While less commonly discussed in the context of everyday phase changes, plasma is a distinct state of matter characterized by highly ionized gas. It involves the separation of electrons from atoms, creating a mixture of ions and free electrons. While the formation of plasma might seem like a chemical process due to the ionization, it's more accurately considered a physical change in the state of matter. The atoms themselves don't change their elemental identity; only their electron configuration is altered. The transition from gas to plasma (ionization) and plasma to gas (recombination) can be reversed under specific conditions, supporting their classification as physical changes.

Examples to solidify the understanding

Let's look at some everyday examples to further illustrate the difference:

Physical Change (Phase Change):

- Melting butter: The butter changes from a solid to a liquid, but it's still butter. The molecules haven't changed chemically; only their arrangement has.

- Boiling water: Water transitions from a liquid to a gas (steam), but it remains H₂O.

- Freezing orange juice: The liquid orange juice becomes a solid, but the components within the juice haven't undergone a chemical reaction.

Chemical Change:

- Burning wood: Wood (cellulose, lignin) is transformed into ash, carbon dioxide, water vapor, and other gases—completely new substances with different chemical structures.

- Rusting iron: Iron reacts with oxygen to form iron oxide (rust), a chemically different substance.

- Baking a cake: The ingredients undergo chemical reactions (e.g., Maillard reaction), creating a completely new substance, the cake.

Conclusion: A Definitive Answer

In conclusion, phase changes are unequivocally physical changes. They involve changes in the physical state of matter, but not changes in its chemical composition. While energy changes accompany these transitions, the fundamental characteristic remains the absence of any alteration in the chemical identity of the substance involved. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to comprehending the behavior of matter and the processes that shape our world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Integrate On A Ti 84

Apr 03, 2025

-

Two Lines Intersecting At A Right Angle

Apr 03, 2025

-

What Is 7 Out Of 15 As A Percentage

Apr 03, 2025

-

Which Kingdom Contains Heterotrophs With Cell Walls Of Chitin

Apr 03, 2025

-

In A Solution The Solvent Is

Apr 03, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Are Phase Changes Chemical Or Physical . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.