What Happens To The Electrons In Ionic Bonding

listenit

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Happens to Electrons in Ionic Bonding? A Deep Dive

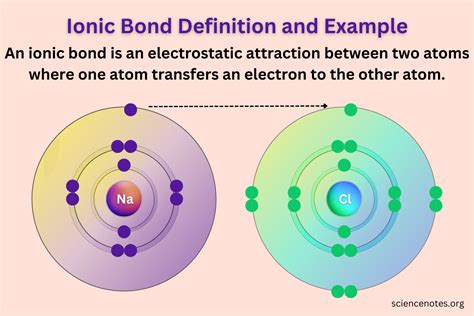

Ionic bonding, a fundamental concept in chemistry, describes the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions. Understanding what happens to electrons during this process is crucial to grasping the nature of these bonds and the properties of ionic compounds. This article delves into the intricacies of electron transfer in ionic bonding, exploring the driving forces behind it, the resulting stable configurations, and the implications for the physical and chemical characteristics of ionic substances.

The Electron Transfer Process: A Foundation of Ionic Bonding

At the heart of ionic bonding lies the transfer of electrons from one atom to another. This transfer doesn't occur randomly; it's a consequence of the inherent differences in the electronegativity of the atoms involved. Electronegativity is a measure of an atom's ability to attract electrons towards itself in a chemical bond. Atoms with high electronegativity strongly attract electrons, while those with low electronegativity have a weaker pull.

When an atom with low electronegativity (typically a metal) encounters an atom with high electronegativity (typically a non-metal), the difference in electronegativity creates an imbalance. The highly electronegative atom exerts a stronger pull on the valence electrons of the less electronegative atom. If this pull is strong enough, it overcomes the electrostatic attraction between the nucleus of the less electronegative atom and its valence electrons. This results in the complete transfer of one or more electrons from the less electronegative atom to the highly electronegative atom.

The Role of Valence Electrons

Valence electrons, the electrons in the outermost shell of an atom, are the key players in ionic bonding. These electrons are relatively loosely held and are the first to be involved in chemical reactions. The transfer of valence electrons is what leads to the formation of ions – charged particles.

The atom that loses electrons becomes a cation, a positively charged ion. This is because it now has more protons (positive charges) than electrons (negative charges). Conversely, the atom that gains electrons becomes an anion, a negatively charged ion, as it now possesses more electrons than protons.

Achieving Stable Octet Configurations: The Driving Force

The driving force behind electron transfer in ionic bonding is the desire of atoms to achieve a stable electron configuration, usually an octet (eight valence electrons). This octet rule, while not universally applicable, provides a useful framework for understanding the stability gained through ionic bonding. Atoms strive to achieve this stable configuration because it represents a state of minimum energy.

Atoms with nearly full valence shells (like halogens with seven valence electrons) readily gain an electron to complete their octet. Conversely, atoms with only a few valence electrons (like alkali metals with one valence electron) readily lose these electrons to achieve a stable configuration, often matching the electron configuration of the nearest noble gas.

Example: Sodium Chloride (NaCl)

Let's consider the formation of sodium chloride (common table salt) as a classic example. Sodium (Na) has one valence electron, while chlorine (Cl) has seven.

- Sodium (Na): Sodium readily loses its single valence electron to achieve a stable electron configuration matching that of neon (Ne). This leaves sodium with 11 protons and 10 electrons, resulting in a +1 charge (Na⁺).

- Chlorine (Cl): Chlorine readily gains one electron to complete its octet, achieving the stable electron configuration of argon (Ar). This results in chlorine having 17 protons and 18 electrons, resulting in a -1 charge (Cl⁻).

The resulting oppositely charged ions, Na⁺ and Cl⁻, are electrostatically attracted to each other, forming an ionic bond. This attraction holds the ions together in a crystal lattice, a three-dimensional arrangement of alternating cations and anions.

Beyond the Octet Rule: Exceptions and Complexities

While the octet rule serves as a helpful guideline, it's important to acknowledge its limitations. Several exceptions exist:

- Transition metals: Transition metals often exhibit multiple oxidation states, meaning they can lose varying numbers of electrons, resulting in ions with different charges. Their electron configurations are more complex, and the octet rule doesn't always perfectly predict their behavior.

- Elements in the third period and beyond: These elements can sometimes accommodate more than eight valence electrons in their outer shells due to the availability of d orbitals.

- Incomplete octets: Some molecules exist with fewer than eight valence electrons around certain atoms, particularly those involving elements like beryllium and boron.

Despite these exceptions, the underlying principle of achieving a more stable electron configuration through electron transfer remains a central theme in understanding ionic bonding.

Properties of Ionic Compounds: A Consequence of Electron Transfer

The transfer of electrons and the resulting electrostatic attraction between ions have profound implications for the properties of ionic compounds:

- High melting and boiling points: The strong electrostatic forces between ions require significant energy to overcome, leading to high melting and boiling points.

- Crystalline structure: Ionic compounds typically form well-defined crystal lattices due to the ordered arrangement of ions needed to maximize electrostatic attraction and minimize repulsion.

- Hardness and brittleness: While strong, ionic crystals are brittle. Applying stress can cause like charges to align, leading to repulsion and fracture.

- Solubility in polar solvents: Ionic compounds often dissolve readily in polar solvents like water because the polar solvent molecules can interact with and effectively separate the ions.

- Electrical conductivity: Ionic compounds conduct electricity when molten or dissolved in water, as the mobile ions can carry electric charge. In the solid state, the fixed ions cannot move freely and conductivity is absent.

Ionic Bonding in Everyday Life

Ionic bonding is not just a theoretical concept; it's integral to numerous materials and processes we encounter daily:

- Table salt (NaCl): A fundamental seasoning, NaCl is a prime example of an ionic compound.

- Bones and teeth: Calcium phosphate, an ionic compound, provides structural strength to bones and teeth.

- Fertilizers: Many fertilizers contain ionic compounds that provide essential nutrients to plants.

- Batteries: Batteries rely on the movement of ions to generate electrical current.

- Electrolytes in bodily fluids: Ions like sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), and chloride (Cl⁻) play crucial roles in maintaining fluid balance and nerve impulse transmission.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Process with Far-Reaching Consequences

The transfer of electrons in ionic bonding is a dynamic process driven by the pursuit of electronic stability. The resulting electrostatic interactions between ions profoundly influence the physical and chemical properties of the resulting ionic compounds, making them essential components in countless natural and manufactured materials. Understanding the intricacies of this process is fundamental to appreciating the diversity and importance of ionic compounds in the world around us. From the salt on our tables to the complex biological processes within our bodies, ionic bonding is a cornerstone of chemistry, with far-reaching consequences. The details explored here offer a comprehensive understanding, extending beyond basic definitions to cover exceptions, real-world applications, and the overall significance of this type of chemical bond.

Latest Posts

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Happens To The Electrons In Ionic Bonding . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.