Proteins Are Made Up Of Monomers Called

listenit

Mar 16, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Proteins Are Made Up of Monomers Called Amino Acids: A Deep Dive into Protein Structure and Function

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, involved in virtually every biological process imaginable. From catalyzing reactions as enzymes to providing structural support as components of the cytoskeleton, proteins' diverse functionalities stem from their intricate structures. But what are these amazing molecules fundamentally made of? The answer lies in their building blocks: amino acids, the monomers that assemble to form the complex polymers we know as proteins.

Understanding Amino Acids: The Building Blocks of Proteins

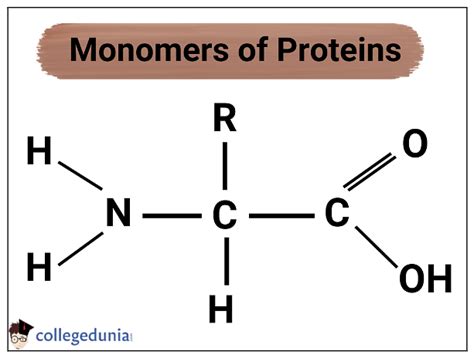

Amino acids are organic molecules characterized by a central carbon atom (the α-carbon) bonded to four different chemical groups:

- An amino group (-NH₂): This group is basic and carries a positive charge at physiological pH.

- A carboxyl group (-COOH): This group is acidic and carries a negative charge at physiological pH.

- A hydrogen atom (-H): A simple hydrogen atom.

- A variable side chain (R-group): This is the unique part of each amino acid, conferring its specific chemical properties.

The R-group is what distinguishes one amino acid from another. It can be a simple hydrogen atom (as in glycine), a methyl group (as in alanine), or a complex aromatic ring (as in phenylalanine). The diversity of R-groups is responsible for the incredible variety of protein structures and functions.

The 20 Standard Amino Acids

There are 20 standard amino acids commonly found in proteins, each with its own unique R-group. These amino acids are categorized based on the properties of their side chains:

-

Nonpolar, aliphatic amino acids: These have hydrophobic (water-repelling) side chains. Examples include glycine, alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, and methionine. These amino acids tend to cluster together in the interior of proteins, away from the aqueous environment.

-

Aromatic amino acids: These have ring structures in their side chains, contributing to their hydrophobic nature. Examples include phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. Their aromatic rings can participate in various interactions within the protein structure.

-

Polar, uncharged amino acids: These have hydrophilic (water-attracting) side chains. Examples include serine, threonine, cysteine, asparagine, and glutamine. These amino acids often reside on the protein's surface, interacting with the surrounding water molecules. Cysteine is unique among this group due to its ability to form disulfide bonds, crucial for protein stabilization.

-

Positively charged (basic) amino acids: These have side chains with a positive charge at physiological pH. Examples include lysine, arginine, and histidine. Their positive charges can participate in ionic interactions within the protein or with other molecules.

-

Negatively charged (acidic) amino acids: These have side chains with a negative charge at physiological pH. Examples include aspartic acid and glutamic acid. Similar to basic amino acids, their negative charges contribute to ionic interactions.

Peptide Bonds: Linking Amino Acids

Amino acids are linked together through a process called peptide bond formation. This involves a dehydration reaction where the carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of another amino acid, releasing a molecule of water and forming a peptide bond (amide bond) between the two amino acids. This bond is a strong covalent bond that holds the amino acid sequence together.

A chain of amino acids linked by peptide bonds is called a polypeptide. Proteins are essentially one or more polypeptides folded into a specific three-dimensional structure. The sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain is called its primary structure, and this sequence dictates all higher levels of protein structure.

Levels of Protein Structure: From Primary to Quaternary

The intricate three-dimensional structure of a protein is crucial for its function. Protein structure is described at four levels:

1. Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Sequence

The primary structure is simply the linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. This sequence is determined by the genetic code, which dictates the order in which amino acids are incorporated during protein synthesis. Even a single amino acid change can drastically alter the protein's structure and function, as seen in mutations leading to genetic diseases. This sequence is crucial because it determines all higher levels of protein structure.

2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The primary structure begins to fold into local patterns called secondary structures, primarily due to hydrogen bonding between the amino and carboxyl groups of the polypeptide backbone. The most common secondary structures are:

-

α-helices: A right-handed coiled structure stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid four residues down the chain.

-

β-sheets: Extended polypeptide chains arranged side-by-side, forming a sheet-like structure. Hydrogen bonds form between adjacent strands. β-sheets can be parallel (strands running in the same direction) or antiparallel (strands running in opposite directions).

These secondary structures are important for creating localized regions of stability and structure within the larger protein.

3. Tertiary Structure: The Overall 3D Arrangement

The tertiary structure describes the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a polypeptide chain, including its secondary structures. This folding is driven by various interactions between the R-groups of the amino acids:

-

Hydrophobic interactions: Nonpolar side chains cluster together in the protein's interior to minimize contact with water.

-

Hydrogen bonds: Hydrogen bonds form between polar side chains.

-

Ionic bonds (salt bridges): Ionic interactions occur between oppositely charged side chains.

-

Disulfide bonds: Covalent bonds form between cysteine residues, strongly stabilizing the protein structure.

The tertiary structure is crucial for the protein's function as it determines the arrangement of its active site (for enzymes), binding sites (for receptors), or other functional regions.

4. Quaternary Structure: Interactions Between Multiple Polypeptide Chains

Some proteins consist of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) interacting to form a functional protein complex. The quaternary structure describes the arrangement of these subunits. Interactions between subunits are similar to those that stabilize tertiary structure, including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and disulfide bonds. Examples of proteins with quaternary structure include hemoglobin and many enzymes.

Protein Folding and Chaperones

The process of protein folding from the linear primary structure to its functional three-dimensional conformation is a complex and dynamic process. It's often assisted by molecular chaperones, proteins that help prevent aggregation and guide proper folding. Incorrect folding can lead to the formation of non-functional proteins or even aggregation, which can be implicated in diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Protein Function: A Diverse Array of Roles

The diverse functions of proteins are intimately linked to their three-dimensional structures. The arrangement of amino acids creates unique binding sites, active sites, and structural elements responsible for their various roles in the cell:

-

Enzymes: Catalyze biochemical reactions by lowering the activation energy. Their active sites bind to specific substrates, facilitating the reaction.

-

Structural proteins: Provide structural support and shape to cells and tissues. Examples include collagen (in connective tissue) and keratin (in hair and nails).

-

Transport proteins: Carry molecules across cell membranes or throughout the body. Examples include hemoglobin (carrying oxygen in the blood) and membrane transporters.

-

Motor proteins: Generate movement within the cell or organism. Examples include myosin (muscle contraction) and kinesin (intracellular transport).

-

Hormones: Chemical messengers that regulate various physiological processes. Examples include insulin and growth hormone.

-

Receptors: Bind to specific molecules and trigger cellular responses. Examples include cell surface receptors and intracellular receptors.

-

Antibodies: Part of the immune system, recognizing and binding to foreign antigens.

-

Storage proteins: Store essential molecules, such as ferritin (storing iron).

Conclusion: The Importance of Amino Acid Sequence

Proteins are essential macromolecules responsible for a vast array of cellular functions. Their remarkable diversity and specificity arise from the precise sequence of amino acids, their monomers. Understanding the properties of amino acids and how they interact to form different levels of protein structure is fundamental to comprehending the intricate mechanisms of life. From the simple peptide bond to the complex interplay of forces stabilizing tertiary and quaternary structures, the journey from amino acids to functional proteins is a testament to the elegance and efficiency of biological systems. Further research continues to unravel the mysteries of protein folding, function, and dysfunction, paving the way for new medical treatments and biotechnological applications.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Radians In A Revolution

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Can Sedimentary Rock Become Metamorphic Rock

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is The Square Root Of 500

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is The Next Number In The Sequence 3 9 27 81

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 10 To The Power Of 7

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Proteins Are Made Up Of Monomers Called . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.