A Flywheel In The Form Of A Uniformly Thick Disk

listenit

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Flywheel in the Form of a Uniformly Thick Disk: A Deep Dive into Rotational Dynamics

A flywheel, a rotating mechanical device used to store rotational energy, finds widespread application in various engineering disciplines. When designed as a uniformly thick disk, its analysis simplifies significantly, allowing for a clear understanding of fundamental concepts in rotational dynamics. This article delves deep into the physics, engineering applications, and design considerations of a flywheel in the form of a uniformly thick disk.

Understanding the Physics of a Uniformly Thick Disk Flywheel

A uniformly thick disk flywheel implies that the mass is evenly distributed throughout its volume. This uniform mass distribution simplifies calculations considerably. Several key parameters govern its performance:

1. Moment of Inertia (I):

The moment of inertia is the rotational equivalent of mass in linear motion. It quantifies an object's resistance to changes in its rotational speed. For a uniformly thick disk of mass M and radius R, the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the disk and passing through its center is given by:

I = (1/2)MR²

This formula is crucial for calculating the kinetic energy stored in the rotating flywheel. A higher moment of inertia indicates a greater ability to store energy at a given rotational speed.

2. Kinetic Energy (KE):

The kinetic energy stored in a rotating flywheel is directly proportional to its moment of inertia and the square of its angular velocity (ω):

KE = (1/2)Iω² = (1/4)MR²ω²

This equation highlights that the energy stored increases quadratically with angular velocity. Therefore, increasing the rotational speed is far more effective in boosting energy storage than simply increasing the mass or radius.

3. Angular Momentum (L):

Angular momentum represents the rotational equivalent of linear momentum. For a uniformly thick disk flywheel, it's defined as:

L = Iω = (1/2)MR²ω

Angular momentum is conserved in the absence of external torques. This principle is exploited in various applications, such as stabilizing spacecraft orientation.

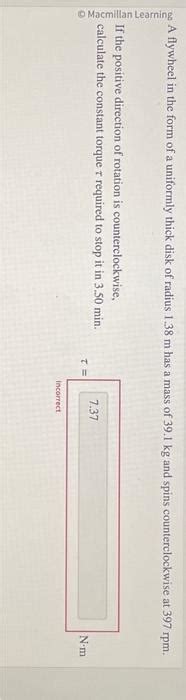

4. Torque (τ):

Torque is the rotational analogue of force. It causes changes in angular velocity. Newton's second law for rotation states:

τ = Iα

where α is the angular acceleration. Applying a torque to the flywheel will accelerate or decelerate its rotation. The magnitude of the torque required depends on the moment of inertia and the desired rate of change in angular velocity.

Engineering Applications of Uniformly Thick Disk Flywheels

The simplicity of analysis and predictable behavior of uniformly thick disk flywheels makes them suitable for a variety of applications:

1. Energy Storage:

This is perhaps the most prominent application. Flywheels can store significant amounts of energy, particularly in situations where intermittent power sources are used. Think of regenerative braking systems in hybrid vehicles where energy from braking is recovered and stored in a flywheel. They are also used in power backup systems and for stabilizing grid fluctuations.

2. Mechanical Power Transmission:

Flywheels can smooth out fluctuations in torque or speed. For example, in stamping presses, a flywheel helps to maintain a relatively constant speed despite variations in the load. This prevents jerky motion and ensures consistent product quality.

3. Gyroscopic Stabilization:

The angular momentum of a rapidly spinning flywheel provides gyroscopic stability. This principle is used in stabilizing devices, like ships' gyroscopes or in aerospace applications for maintaining spacecraft orientation. The higher the angular momentum (and thus, the speed of rotation), the better the stabilization.

4. Mechanical Clocks:

Traditional mechanical clocks rely on the controlled release of energy from a flywheel-based spring mechanism. The flywheel regulates the rate of energy release, ensuring precise timekeeping. While modern clocks use different technologies, the fundamental principle persists.

Design Considerations for Uniformly Thick Disk Flywheels

Several factors need careful consideration when designing a uniformly thick disk flywheel:

1. Material Selection:

The choice of material significantly impacts the flywheel's performance and lifespan. High tensile strength, high yield strength, and high fatigue resistance are crucial properties. Common materials include high-strength steel alloys, carbon fiber composites, and advanced ceramics. The material density also influences the moment of inertia for a given mass and radius.

2. Dimensions:

The diameter and thickness of the disk dictate the moment of inertia and, consequently, the energy storage capacity. A larger diameter and thicker disk generally lead to higher energy storage but also increase weight and manufacturing complexity. Finding an optimal balance is critical.

3. Shaft Design:

The shaft connecting the flywheel to the rest of the system must be robust enough to withstand the torques and stresses generated during operation. Shaft design depends on the flywheel's size, operating speed, and the magnitude of the applied torques. Fatigue failure is a major concern, requiring careful analysis and design.

4. Bearings:

High-quality bearings are essential for minimizing frictional losses. Low-friction bearings, such as magnetic bearings or advanced roller bearings, are crucial for maximizing efficiency and extending the flywheel's lifespan. The bearing selection depends on the operating speed, load, and environmental conditions.

5. Stress and Strain Analysis:

The stresses and strains within the flywheel during operation must be carefully analyzed to prevent failure. Finite element analysis (FEA) is commonly used to model the stress distribution and identify potential weak points. This analysis is essential for ensuring the structural integrity and safety of the flywheel.

6. Safety Measures:

Flywheels operating at high speeds pose a significant safety risk. Robust containment systems, such as protective housings, are necessary to prevent catastrophic failure and potential harm. Emergency braking mechanisms are also crucial to quickly bring the flywheel to a standstill in case of malfunction.

Advanced Considerations and Future Trends

The field of flywheel technology is constantly evolving. Here are some advanced considerations and future trends:

1. Composite Materials:

Advanced composite materials, such as carbon fiber reinforced polymers, offer high strength-to-weight ratios compared to traditional metals. These materials are enabling the development of lighter and more energy-dense flywheels.

2. Magnetic Bearings:

Magnetic bearings offer virtually frictionless support, significantly reducing energy losses and extending the flywheel's operational life. However, they are more complex and expensive than traditional bearings.

3. Advanced Control Systems:

Sophisticated control systems are crucial for efficient energy management and safe operation of flywheels. These systems manage energy storage, charging, and discharging processes, optimizing performance and safety.

4. Hybrid Systems:

Integrating flywheels with other energy storage technologies, such as batteries, can create hybrid energy storage systems that combine the advantages of both. This approach can improve overall system efficiency and performance.

5. Applications in Renewable Energy:

Flywheels are finding increasing application in renewable energy systems, such as wind and solar power, to smooth out intermittent power generation and improve grid stability. Their ability to store and release energy quickly makes them valuable assets in these systems.

Conclusion

A flywheel in the form of a uniformly thick disk represents a fundamental concept in rotational dynamics with numerous practical applications. Its analysis simplifies due to the uniform mass distribution, making it a valuable tool for understanding basic principles and building more complex rotational systems. However, careful design considerations are crucial to ensure its safe and efficient operation, particularly when dealing with high speeds and energy densities. Ongoing research and development in material science, bearing technology, and control systems are constantly expanding the capabilities and applications of flywheel technology, making it a key player in various industries for years to come.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

In Which Layer Of The Atmosphere Does The Weather Occur

Mar 20, 2025

-

What Is 60 In Decimal Form

Mar 20, 2025

-

64 Oz Is Equal To How Many Pounds

Mar 20, 2025

-

How Far Is Mars From The Sun In Au

Mar 20, 2025

-

The Monomers Of Nucleic Acids Are

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Flywheel In The Form Of A Uniformly Thick Disk . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.